The Desert Philosopher

A brief introduction to the Evagriana

In this newsletter you will read about:

The Evagriana, the writings of Evagrius Ponticus

Logismoi (afflictive thoughts) and noēmata (virtuous thoughts)

The method of antirrhesis, the “response” to afflictive thinking

Discernment (diakrisis) and a careful observation (paratēresis)

The relation between practice (praktikē) and contemplation (theōria)

Many other wondrous terms, including apatheia (equanimity), hesychia (stillness), anachoresis (withdrawal), and agape (unconditioned love).

I was struck (but in retrospect not surprised) by the interest in and enthusiasm for Evagrius I heard from the crowd during the Q&A of my talk at The Alembic, so I prepared this little primer for those folks still interested in learning more.

It’s certainly not complete—one must respect Substack for what it is—but it will hopefully lead you readers down some interesting trails for thought.

As always, if you enjoy The Base Camp, consider forwarding this email to your friends and colleagues, or just share this link with your networks.

The “desert philosopher” Evagrius Ponticus (c. 345-399 AD) was a Christian monk, ascetic, and theologian. He is best known for his teachings on prayer, asceticism, and his analysis of logismoi, or “afflictive thoughts,” and noēmata, “virtuous thoughts.”

As we’ll see, the differentiation between the two is anything but binary, but this initial distinction offers us a way into the Evagrian method.

Evagrius observed that among the many afflictive and virtuous thoughts, one finds eight primary types of each. Among the afflictive thoughts he noted gluttony, lust, avarice, sadness, anger, acedia, vainglory, and pride.

Among the virtuous thoughts he included temperance, prudence, poverty, joy, charity, patience, moderation, and humility.

The modern reader may wince when I add that for Evagrius the afflictive thoughts are the product of demonic influence, while the virtuous thoughts have an angelic source—with the human balanced between—but this typology is key to understanding the Evagrian psychology.

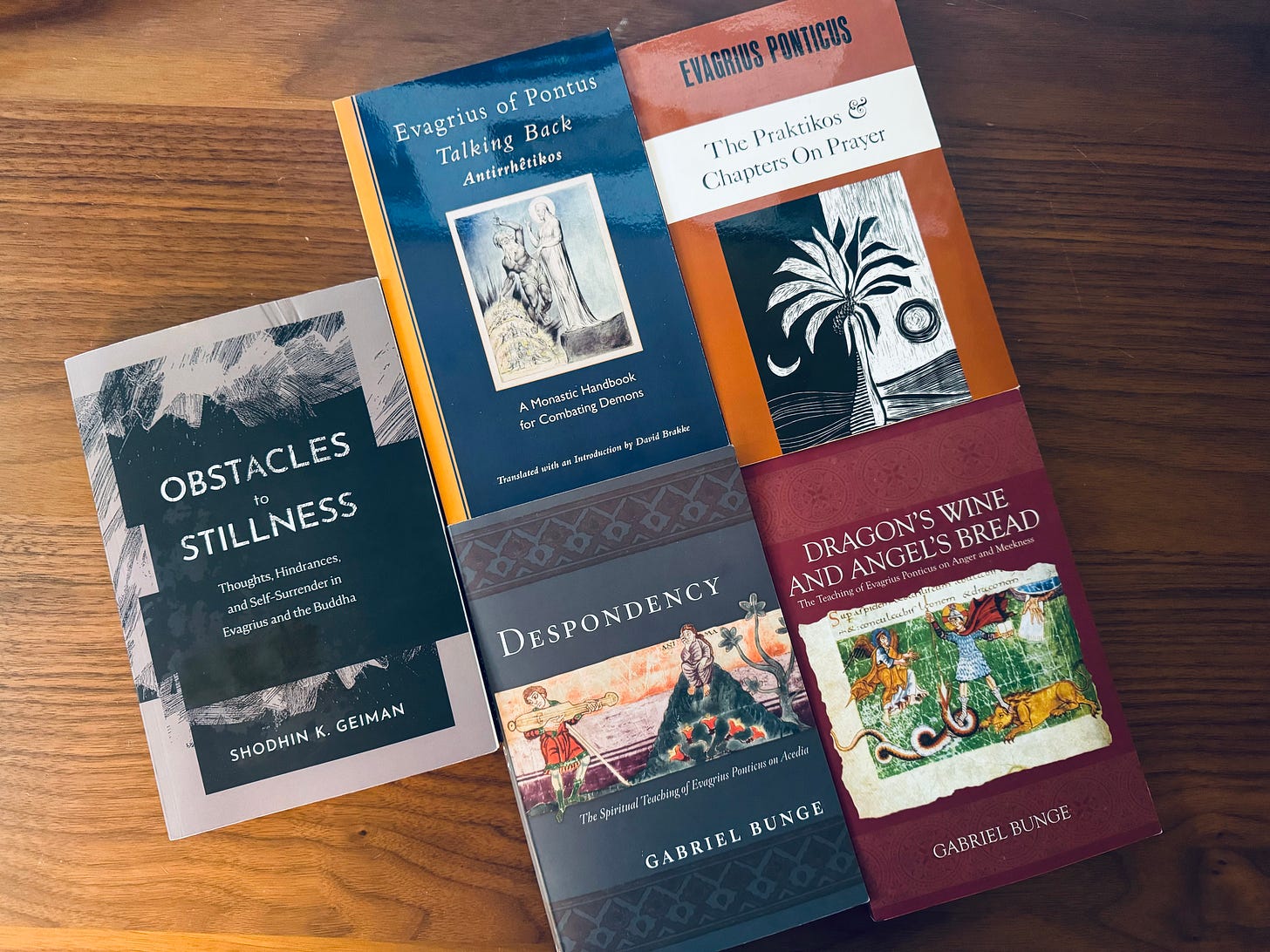

The nature and effect of these thoughts, as well as their relation to one another, are treated in several of his texts, including Eight Thoughts, The Praktikos, Chapters on Prayer, and Antirrhêtikos. These are more preliminary works aimed at monks early in their ascetic developments. (I’ll more to say about his more advanced teachings below.)

Afflictive Thoughts

According to Evagrius, logismoi are thoughts or thought patterns that can lead a person away from virtue. The verb logizomai means “to reckon,” “to calculate,” “to reason,” or “to consider.”

In this sense, the logismoi involve a kind of internal, though distorted, reasoning process. In other words, when a logismos arises in the mind, it often presents itself as a rational argument or justification for a particular course of action or way of thinking.

This is where the idea of logismoi as “afflictive” thoughts comes in—they are (seemingly) rational justifications for pursuing some kind of self-harm or harm oriented towards other people.

These thoughts are seen as afflictive because they can lead us into spiritual and moral hazard if we follow their logic. They afflict us by clouding our judgment, stirring up disordered emotions, and leading us away from more virtuous decision making.

For example, acedia (“despondency” or “listlessness”) is an afflictive thought or mood that presents itself as the rational observation or legitimate feeling that one’s efforts at whatever task are in vain—that progress is unattainable, that the goal isn’t worth it anyway, that there are better things to do (like, say, falling asleep).

For Evagrius, the term arises in reference to the life and challenges of the monk living a monastic life, but we shouldn’t see the term as limited to monastics alone.

For lay people, acedia can manifest as a general sense of apathy and dissatisfaction with one’s spiritual life and daily responsibilities. Acedia can also prompt a pull towards worldly comforts and pleasures as a means of coping with spiritual emptiness. At its core, it represents a disengagement from the challenges and commitments of one’s life, both spiritual and practical, leading to a state of feeling stuck or stagnant, characterized by a lack of purpose, direction, and motivation.

The point, is the whole feeling is ultimately a deception. One’s tasks are worthwhile, the effort will yield fruit, and progress is attainable!

In the Evagrian tradition, the goal is not simply to suppress or ignore these thoughts, but rather to learn to recognize them for what they are—false reasonings that need to be countered with wisdom and virtue.

The afflictive nature of logismoi is tied to their deceptive and disordered nature.

They afflict us by presenting themselves as reasonable or justified, when in fact they are leading us away from healthy thinking and toward spiritual, psychological, or physical harm. The task of the spiritual life is to learn to see through these false reckonings and to align our thoughts and actions with virtue and goodness.

This is done in a variety of ways, including through prayer and meditation, but also through cultivating counter-vailing feelings or actions—fasting counters gluttony, perseverance counters acedia, humility counters vainglory, charity overcomes avarice.

This requires a kind of inner watchfulness or discernment (diakrisis) and a careful observation (paratēresis), where we learn to spot the logismoi when they arise.

Discernment and Observation

Discernment and observation are central to this process because it’s simply not always obvious which category any given thought may fall into, hence the need for instruction, spiritual direction, and appeals to handbooks and traditions.

At the level of mental representations, Evagrius roots his strategy in a phenomenological observation: While the mind may associate one thought or representation with another, sometimes drawing excessive associations with the rapidity one feels in anxiety or psychological turmoil, the mind doesn’t, as a matter of fact, hold multiple thoughts together at once.

The mind holds only one representation at a time, even if in a fleeting way.

This stream of consciousness, of one thought leading to the next, offers an opportunity for the Evagrian practitioner. Namely, since only one thought can be held at a time, one thought can intentionally interrupt another. The method described in Antirrhêtikos is precisely this maneuver of guiding afflictive thought towards virtuous thought through intentional acts of association.

Kevin Corrigan picks up these theme in Evagrius, noting how thoughts can both “cut” or “be cut” by other thoughts. Elsewhere Evagrius describes this as the art of antirrhesis, which means both “contradiction” or “response.” The afflictive thought is contradicted or responded to by introducing a countervailing sentiment. For the Christian Evagrius, these responses are drawn from prayer, scripture, and psalm.

Thus just as there are countervailing actions to afflictive behaviors, there are also thoughts that counter other thoughts. In this sequence of thoughts and counter-thoughts, one can see clearly the Evagrian appeal to martial metaphors. One is engaged in a combat with afflictive thought summed up in what Jacob Given aptly calls tactical desert empiricism, a “spiritual athleticism” suited to such combat.

In this assessment a further fact grows clear in reading Evagrius. The logismoi manifest differently in different people, depending on one’s disposition and circumstance. Lay people, monks living in community (cenobites), and solitary monks (anchorites) all experience different types of afflictive thoughts.

For instance, lay people living out in the social world may experience the temptation of material wealth, but for the monk who has already renounced these possessions, the sphere of attachment to wealth and goods is mostly foreclosed, while the sphere of mental life is opened up greatly, making the battle a substantially more interior one, owing to the enhanced emphasis on prayer and meditation.

These afflictions also vary from person to person based on temperament.

If for example you are an introverted, highly intellectual person, then the afflictions may take the form of rumination, distracted ideas, and negative thinking. In a very extroverted and gregarious person, they may take the form of obsession with gossip, status anxiety, or other social or interpersonal maladies.

Or perhaps you’re the lucky type of person who experiences both.

Along these lines, Evagrius also included the two large categories of irascible and concupiscible passions. The irascible passions are related to the soul’s capacity for anger, aggression, and aversion. The concupiscible passions are related to the soul’s capacity for desire, appetite, and attraction. These passions also have healthy forms as courage and patience and temperance, charity, and self-restraint, respectively.

In this sense, it’s not that these larger categories are by themselves positive or negative. Rather, Evagrius follows a distinctly Platonic understanding of the soul and its partitions, so that the rational faculty (logistikon), along with the irascible (thymikon) and concupiscible (epithymetikon) faculties are hemmed together, and work together, in more or less healthy ways, depending on their development through practice.

Still, any one individual may be more prone to irascible or concupiscible passions in their unhealthy expressions, and this is what the practices seek to amend.

Here’s Gabriel Bunge on these points:

Lay people living in the world are tempted for the most part by concrete material things; those living together in a community and the cenobites, who live together in a narrow space, are tempted above all by their negligent brethren. There are all the small and large frictions of life in common, which indeed one is able to avoid far less in a monastery than in the world. The anchorites, on the other hand, who have given up not only material things, but largely also association with others, are tempted mostly by “thoughts,” that is, by all the images, representations, and so forth that are inevitably left behind in their memories, not only of material things but also of inter-human connections and their problems. These “thoughts” or memories represent the passions in their purest form, so to speak, detached from any direct concrete occasion. Evagrius declares pertinently that this struggle, “man against man,” is by far the toughest, since no human being can be as malicious as a demon.

In other words, the attack surfaces open to afflictive thoughts tend to grow more subtle, and more “interior,” as one travels further down the path of asceticism and renunciation, but they never disappear entirely.

Practice and Contemplation

These more subtle aspects of the monk’s development are present throughout the Evagriana, but they hold a pronounced place in more advanced texts, like On Thoughts, a deep investigation (or phenomenology, I would say) of the subtle emergence and interrelationships between different types of thoughts and their consequences.

I recommend Robert E. Sinkewicz’s commentary and translation on this text for readers who want a deeper diver into this sophisticated psychology.

Throughout On Thoughts, Evagrius is concerned with the way in which the logismoi shape the overall field of consciousness, influencing perception, emotion, and volition. His goal is not merely to catalog these experiences, but to understand their structure and dynamics, and to develop practical strategies for navigating them in the context of the spiritual life.

At the same time, Evagrius’s work is not a purely descriptive phenomenology, but a normative one. It is guided by a specific spiritual telos, the ideal of apatheia, or equanimity. The phenomenological analysis of the logismoi is ultimately in service of this transformative goal, of reshaping the structures of consciousness in accordance with the ideals of the Christian life.

But the soul often has trouble entering into prayer and meditation under certain circumstances, and indeed some circumstances make both nearly impossible.

The ideal of apatheia is thus approached from multiple perspectives, but the practitioner advances towards this goal through the dual methods of ascetical practice (praktikē) and contemplation (theōria).

Praktikē involves the countervailing maneuvers we discussed previously, and even before those, a set of preparatory plans that begin with anachoresis, the monk’s withdrawal from secular life. This withdrawal is often accompanied by a series of life changes aimed at simplifying the monk’s world and can include things like keeping an ascetic diet, avoiding the accumulation of goods or wealth, abstaining from idle preoccupations, and holding to careful social associations.

I am neither a monk nor a renunciate anchorite, but even for a lay person like myself the benefit of some level of simplification of this kind seems evident.

In any case, the withdrawal is placed in the service of affording the possibility of hesychia (stillness, or what Evagrius himself calls “a state of deep peace and inexpressible joy”). These practical actions are sometimes said to “guard” hesychia, making its manifestation and sustainment more likely.

Hesychia, in turn, is something like the precondition for (or environment within which) contemplation (theōria) can occur. The monks are in this sense setting themselves up for theōria through praktikē, and through theōria are attaining to deeper levels of insight and development that then modify future modes of praktikē.

This cycle, some would say, is an endless progression into unconditional love (agape). As Evagrius puts it: “Agape is the progeny of apatheia. Apatheia is the very flower of ascesis.” And so the circle continues without end.

The Evagriana, introduced here in the briefest of forms, offers, then, a profoundly rich set of resources for individuals interested in pursuing a more deeply healing and contemplative life. (Nota bene: Readers and practitioners of Buddhist ways of life, or those of us interested in comparative religion and philosophy in general, may find a few additional gems in Shodhin K. Geiman’s recently published work Obstacles to Stillness, where Geiman explores parallels between Evagrian afflictive thoughts and the “hindrances” to liberating insight catalogued in Buddhist contemplative practices.)