In this newsletter you will find discussions of:

Middle English mysticism

The Cloud of Unknowing

Aristotle’s On the Soul

Noēsis (contemplation) and Dianoia (thinking)

There are resources in these traditions for thinking about our own thinking, resources that are sometimes lost in our modern appropriation of these terms and concepts.

More often than not, they are lost altogether.

My aim here is to open up this wider space of contemplative transformation so that we might approach our own practices differently, or recover some older ones.

Mind is not reason, mind contains reason.

If you enjoy The Base Camp, consider forwarding this email to your friends and colleagues, or just share this link with your networks.

What watches reason?

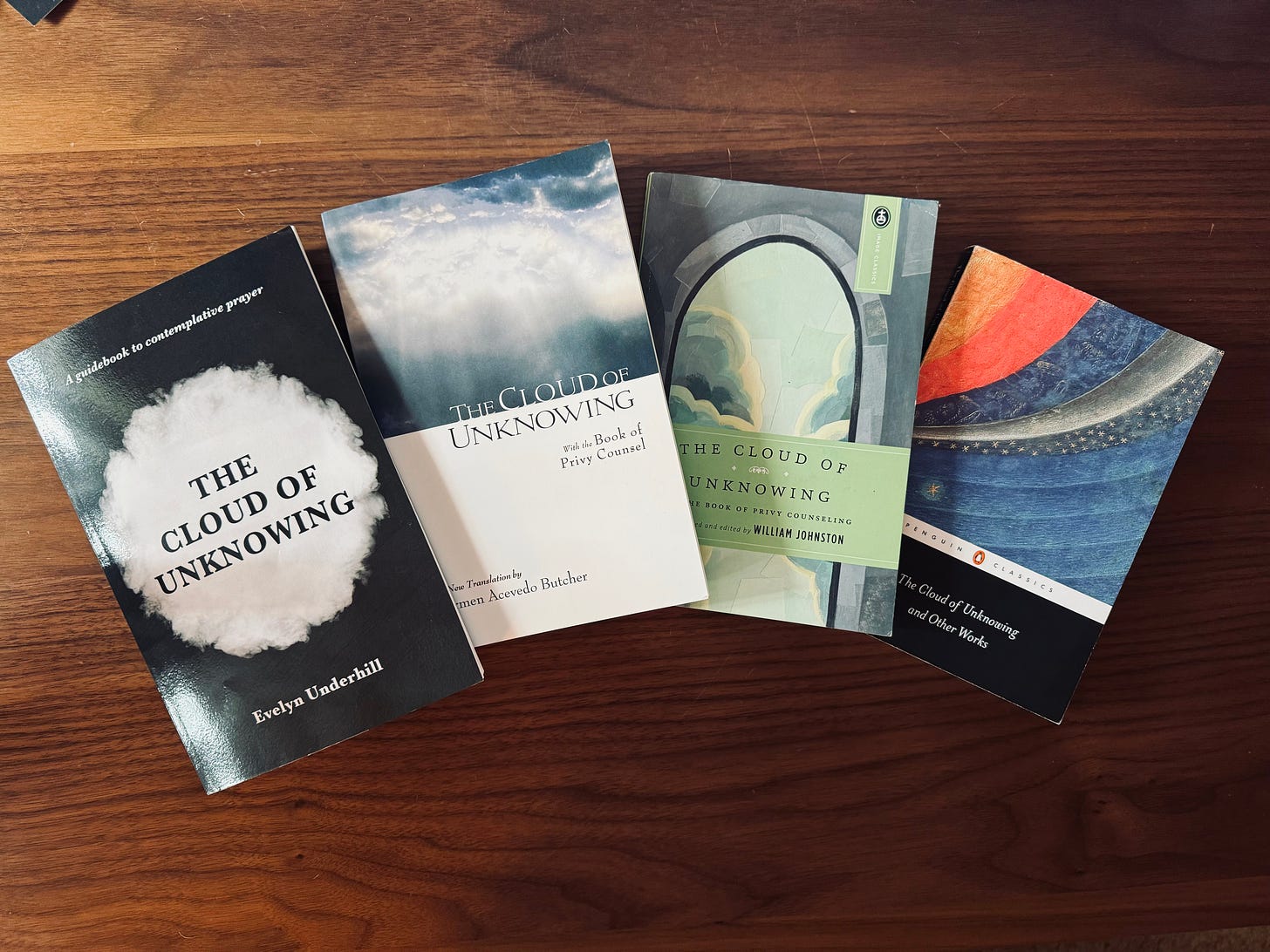

For the author of The Cloud of Unknowing, the answer in Middle English is the familiar looking word, mynd. Scholars have translated this word in a few different ways. The most similar to our modern English is “mind,” but the alternatives include “memory” and “consciousness.” (I’ve included the translations at the end of the essay.)

We have no direct modern correspondence for mynd, but consciousness may be the best option since the original word tries to mark a space for memory and awareness, rather than simply thinking or reasoning. Consciousness is a “knowing or perceiving within oneself, sensible inwardly, aware,” as the etymology has it.

Mind seems more straightforward, but if we want to use that word as the appropriate translation, then we shouldn’t read it in the sense of the “mental faculty, the thinking process.” What the Cloud author means by mynd is more subtle; it comprehends (unites, gathers, perceives) the thinking process, but it is not the activity of thinking itself.

On this view, mynd (mind) is not reson (reason) or thinking.

As the Cloud author says, mynd “has no proper activity of its own,” but “contains and embraces within itself” the other faculties of the soul, including reason, will, imagination, and sense-perception, as well as “the objects on which they work” (Chapter 63). Mynd is in this sense a passive ground the other faculties work from.

It is this kind of passive but encompassing awareness to which contemplation points.

Below, I am going to explore what mynd means for us today, along with the practices of contemplation that are associated with it. Before I do that, though, I want to offer a little more context for the text in which these themes arise.

The Handbook Tradition

The Cloud of Unknowing is an anonymous work of 14th century Middle English Christian mysticism. The text is both philosophical, drawing from traditions of neoplatonism, and religious, taking as a primary influence the 5th century Theologia Mystica of Dionysius the Areopagite.

While we don’t know who the writer is, the learnedness suggest a person of training, perhaps a priest or a theologian, and certainly an adept contemplative. More than philosophy or religion as doctrine, though, The Cloud is a guidebook for spiritual direction whose orientation is that of contemplative prayer and apophasis.

This is a practical manual.

The Cloud Author is joined by other theologians, mystics, and solitaries of this period, including Richard Rolle, Walter Hilton, Julian of Norwich, and Margery Kempe. These writers are the Middle English mystics, though scholars of the period will tell you that this naming is an anachronism unknown to the people of 13th and 14th century England. The modern revisionism aside, the group is distinct in its wedding of scholarship with contemplation and practical communication.

The texts are written in the style Bernard McGinn calls the handbook tradition.

That is, they belong to a group how-to texts often written in the vernacular (i.e., not in Latin, but in Middle English, in this case) that include practical instructions (for contemplative prayer, in this text), guidance on how to navigate those practices (discretion in their use and misuse), and philosophical and theological context (in the form of excerpts or summaries) of relevant preceding ideas (from scripture, theology, and philosophy). The style is often teacher-to-student, written as spiritual direction.

Though these texts have a practical style, it would be too much to say that these were simply popularizations of more complex intellectual works. They do presuppose a history of study and practice. It’s just that their overall tone and vernacular language, along with their practical orientation, made them more accessible. Evelyn Underhill in the introduction to her translation, describes the Cloud Author’s style this way:

What, then, were his special characteristics? Whence came the fresh colour which he gave to the old Platonic theory of mystical experience? First, I think, from the combination of high spiritual gifts with a vivid sense of humour, keen powers of observation, a robust common-sense: a balance of qualities not indeed rare amongst the mystics, but here presented to us in an extreme form. In his eager gazing on divinity this contemplative never loses touch with humanity, never forgets the sovereign purpose of his writings; which is not a declaration of the spiritual favours he has received, but a helping of his fellow-men to share them. Next, he has a great simplicity of outlook, which enables him to present the result of his highest experiences and intuitions in the most direct and homely language. So actual, and so much a part of his normal existence, are his apprehensions of spiritual reality, that he can give them to us in the plain words of daily life: and thus he is one of the most realistic of mystical writers. . . . A skilled theologian, quoting St. Augustine and Thomas Aquinas, and using with ease the language of scholasticism, he is able, on the other hand, to express the deepest speculations of mystical philosophy without resorting to academic terminology.

Here summed up, then, are the Cloud Author’s unique traits—influences from Plato, Augustine, and Aquinas (and centrally, Dionysius the Areopagite, not mentioned here), the synthesis of scholarship and contemplation, a practical and common-sense bent mixed with learned terminology, but with the avoidance of jargon.

This style is no doubt why the book is still widely read in the 20th and 21st centuries.

Saying and Unsaying

The Cloud of Unknowing is itself written in the form of a letter aimed at a younger contemplative. I have written before about the method of contemplative prayer this text guides us through. In that essay, I wanted to draw attention to the contradiction held in the practice given, namely, that the text undoes the vocabulary in which it is written because its aim is to undo the apparatus of language itself.

This is done so that one can encounter in radical simplicity the God who transcends not only human language and understanding, but all representation through perception, sensation, or reasoning, including through your own sense of self. The contradiction is that reading, studying, and praying remain important preparatory acts for this ultimate letting go, but it is through their negation that ultimately “the soul is made one with God,” in the Cloud Author’s language, and so that “we come to rest in a more fundamental experience of being alive,” as David Collins wrote about so eloquently for The Side View.

There is a practical and epistemological sense to this approach. Our intellectual knowing breaks down at a certain transcendent altitude but our loving devotion keeps going. While the emphasis is on the apophatic divestment of sense, word, and image (the “unsaying” of all three), there is a kataphatic (“saying”) dimension here insofar as all three play some role in preparing the ground for the darkness of contemplative silence that goes before and continues beyond them.

For the Cloud Author, then, while we may speak of a dialectic of saying and unsaying, it is this contemplative silence that ultimately breaks the dialectical mode in reverent loving affection that exceeds intellectual delineation, as a kind of loving–attending. This placing of loving over intellectual knowing is bound up with the discussion I began with on mynd and the practices of contemplation associated with it.

I want to focus in the rest of the essay on this account of mynd in the Cloud Author’s text. Mynd shows up in an interesting way here owing to the handbook genre of practical instruction that the text is written in. The handbook style—along with the author’s instructions to explore and investigate these practices and their results for oneself—makes the contemplative ascent of the text available to phenomenological exploration, as a demonstration more than an argument, even though these Middle English authors did not use the more recent language of phenomenology.

Thought and Contemplation

There is a telling relationship between the language of instruction and the wordlessness of the aimed for goal. Aside from the practices themselves, the language used opens out into this implicit phenomenology of the Middle English soul, a soul that finds similar descriptions in Augustine but also in Aristotle and Plato (hence the Dionysian integration of Christian and Platonic apophaticism).

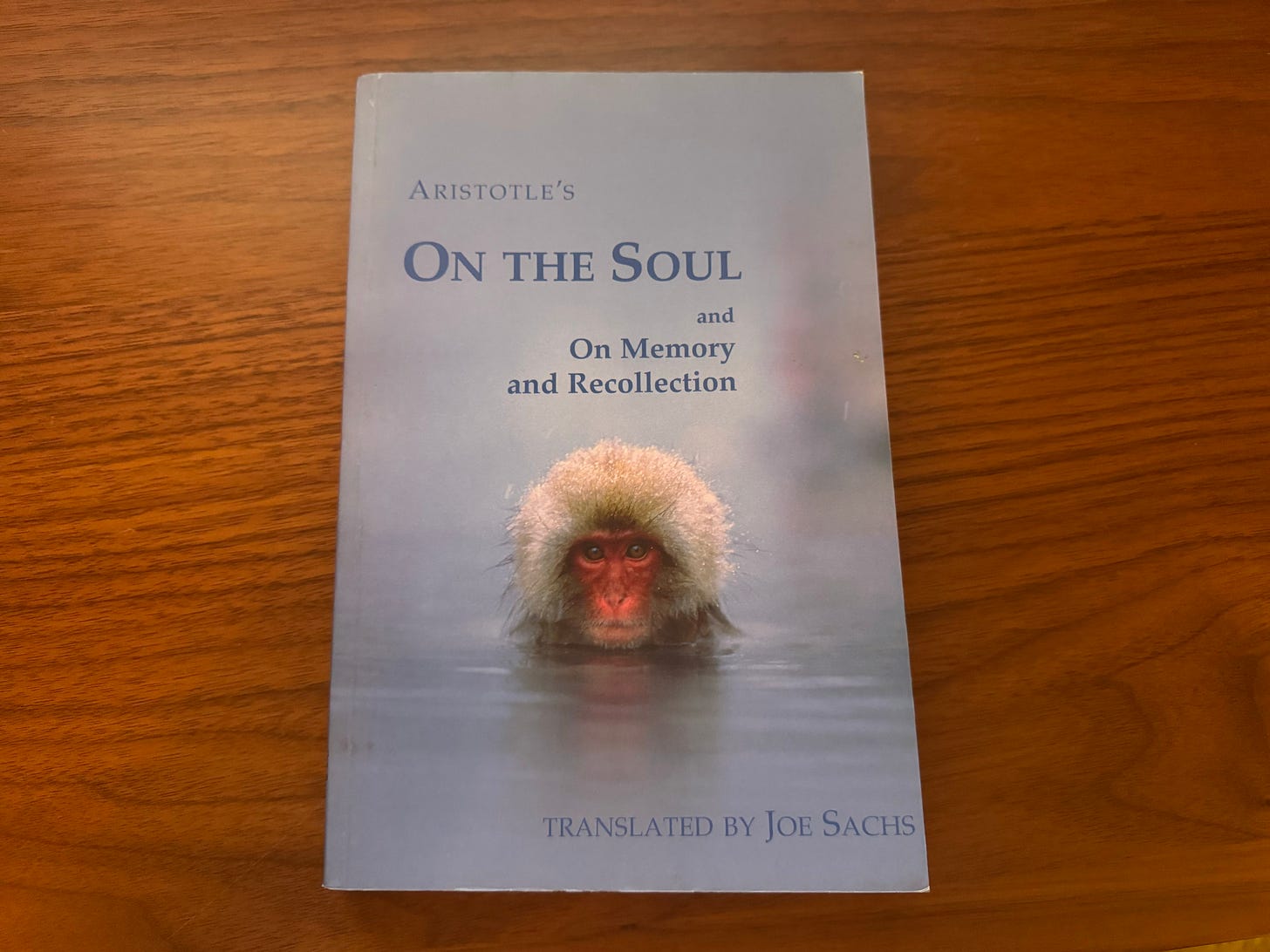

In Augustine, this distinction shows up in the Latin nosse (mind) and cogitare (thinking). As with the Cloud Author’s distinction between mynd (mind) and reson (reason), nosse and cogitare share something of a figure–ground relation. Nosse is holistic, passive, and encompassing. Cogitare is linear, active, and directed. The same relation shows itself in the earlier Greek notions of noēsis and dianoia, a distinction we find articulated in Aristotle’s On the Soul. I quote the following passage from Joe Sachs’s translation too often, but its too succinct not to share in this context again, especially insofar as Sachs brings forth the interwoven character of the two modes.

In this context, Sachs discusses what he calls the “twofoldness” of discursive and contemplative thinking. In this image we find several noteworthy characteristics of noēsis and dianoia—that noēsis is thinking that considers things as “indivisible and whole” as opposed to dianoia, which thinks things in a linear fashion “step-by-step,” part by part. The contemplative thinking of noēsis, is more like a resting repose than than the active motion of dianoia. In this view, noēsis stands in relation to dianoia as its foundation, the means by which dianoia’s operations are framed and contextualized, offering sense and meaning to its ruminations. I quote Sachs in full in these points:

What is this intellect that is so difficult to locate? It is that which thinks things as indivisible and whole, as distinct from thinking them step-by-step in time (430a 26), so that its thinking is more like rest than motion (407a 32-33). This contemplative thinking (noēsis) of the intellect (nous) thus stands opposed to thinking things through (dianoia), but it also stands beneath the act of thinking things through and makes it possible. Every judgment is an external combination of a separated subject and predicate in our discursive thinking, but is simultaneously held together as a unity by the intellect (430b 5-6). That is why Aristotle says that the contemplative intellect is that by means of which the soul thinks things through and understands (429a23). Its thinking is the foundation upon which all other thinking proceeds, just as having our feet on the ground is one of the conditions of our walking. Exclusively discursive thinking that could separate and combine, but could never contemplate anything whole, would be an empty algebra, a formalism that could not be applied to anything. In human thinking, at any rate, the activities of reasoning and contemplation are rarely disentangled.

Today we tend to thinking of mind as thinking and thinking as reasoning but as this discussion shows this is not the whole of what mind is or does. Moreover, There is an important sense in this account that contemplation is always already happening.

You’re just more or less attuned to it, more or less present to it, more else able to see and be transformed from that perspective, and this is what I think we today ought be more present to, the already happening fact of human contemplation. In this sense, traditions of contemplative prayer offer not only pathways into transformative mystical experiences of God and the divine but also into different states of being and thinking that disclose this world in different ways, ways that our current culture need but often underplay or dismiss altogether. The handbook tradition offers us a way to relate to these practices and disseminate them—in a new vernacular—once again.

But don’t take my word for it.

Instead, follow the Cloud Author and go and look for yourself.

Notes

* Middle English is a form of English language spoken and written between about 1100 and 1500 AD. It separates Old English (Anglo-Saxon) and preceded Early Modern English. It's a regional and vernacular language full of variation and improvisation. I'm not an expert in the history of languages or in linguistics, but I find Middle English strange, fascinating, and familiar all at once. It's like a next-door world leaning into this one. It's so close to modern English but so obviously the product of a different mind, a different aesthetic, a different time.

* Included here are the relevant translations of Chapter 63 of The Cloud of Unknowing:

Mynde is soche a mighte in itself, that properly to speke and in maner it worcheth not itself. . . . And on none other wise it is seide that the mynde worcheth, bot yif soche a comprehencion be a werke. (Rochester)

Consciousness in itself is a faculty of such a kind that, so to speak, it has no proper activity of its own. . . . and it cannot be said to be active unless that containing is an activity. (Penguin)

Memory is such a power in itself, that properly to speak and in manner, it worketh not itself. . . . unless such a comprehension be a work. (Ingram)

Mind . . . is not properly said to work but to understand. (Image)