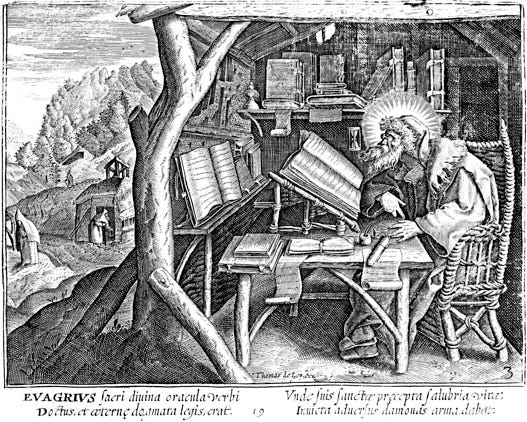

This is a short addendum to my previous essay on Evagrius.

In that essay, I omitted a crucial aspect of the Evagrian method, namely, the practice of self-observation (nēpsis). Below I discuss nēpsis and its relation to Stoic practices of examination and earlier Greek imperatives to “know thyself” (gnothi seauton) and “care for oneself ” (epimeleia heautou), with attention to the difficulties both practices present, especially in regards to philautia (“self-love” or “self-obsession”). This type of attention increases our agency concerning the influences that shape our thoughts, and is thus essential to developing our capacity for free will.

As always, if you enjoy The Base Camp, consider forwarding this email to your friends and colleagues, or just share this link with your networks.

One way to think of the Evagrian method is as a subtle phenomenology of the formulation of our mental representations as we form them, and whether or not we assent to them.

The Stoics also have a similar method.

For the Stoics, the examination of representations was primarily a matter of aligning one’s judgments with reason and nature. They believed that the cosmos was permeated by a divine logos or rational principle, and that human beings could achieve eudaimonia (flourishing or well-being) by living in accordance with this rational order.

The Christian Evagrius adopts a similar method, but for him there is a much greater effort to track the subtle external forces that influence the formation of our representations—the autonomous “afflictive” or “virtuous” thoughts, respectively.

For Evagrius, the cosmos is populated by different ends or aims (teloi, if you like)—beings, values, or ideas that draw our thought in different directions, some healthy and virtuous, others hazardous and corrupt.

The manipulation of mental representations, the distortions of memory, the influence on the reasoning faculty, the intentional evocation of the passions, affliction through dream imagery, if not the total fabrication of dreams—these are the sites of attack at the level of the individual’s interior life.

These influences attach themselves to our bodily nature, our emotional life, and our intellectual thinking, influencing not only the character of each moment of our understanding but also the movement from one representation to the next.

And the same holds true also for representations of our own bodily and interior life.

Here is Evagrius in On Thoughts on the process by which we come to form representations of our own bodily and sensory life:

One should start from the proposition that the mind receives naturally the mental representations of sensible objects and their impressions through the instrumentality of this body of ours. Whatever maybe the form of the object, such is necessarily the image that the mind receives, whence the mental representations of objects are called copies because they preserve the same form as them. So just as the mind receives the mental representations of all sensible objects, in this way it receives also that of its own organism—for this too is sensible.

In other words, we form representations of our own “self” in each moment, though Evagrius (and the Greek philosophers before him) would have referred to the need to tend to the soul (psychē), or even the dynamism between soma (body), soul, (psychē), and nous (mind) rather than to our modern notion of a “self.”

Regardless, it is in these microscopic moments—where the field of rough sensibility is converted into the representations we take to be our “situation,” how we judge or understand things to be—where the influence begins.

This subtle transition from sensibility into representation is why the practice of paying attention to yourself, especially at this level where thoughts and feelings are first taking shape, becomes so important. Attending to yourself is in this way one of the root practices from which the other Evagrian maneuvers grow.

These moment-to-moment conversions of sensation into perception and understanding are in turn what require our inner observation (nēpsis).

The is mode of attention helps develop our agency, or free will, which is essential to the Evagrian method and to his larger Christian ethic as a whole. It is not afflictive thinking by itself that leads us into malady but our decision to pursue those chains of reasoning. For if one cannot pay attention to oneself, then one will remain blind to the forces that shape and influence the construction of one’s own representations, and thus one’s actions and practices of betterment (or their absence).

The sources of our representations are in this way internal to us (in the sense argued for by the Stoics) but also external to us, owing to their openness to influence by higher and lower natures, the beings or teloi I referenced above.

We have here, then, an example of the Delphic and Socratic dictum “know thyself” (gnothi seauton) expanding out into a field where “the self” is open to subtle influences that require spiritual training and preparation to understand and then move in the right direction.

I noted in the previous essay that for Evagrius afflictive thoughts come in the eight primary forms of gluttony, lust, avarice, sadness, anger, acedia, vainglory, and pride. What I didn’t note there is that for Evagrius afflictive thinking is rooted in a single more primary act—philautia—which bears on this dynamic of self-knowledge.

As for some many other terms in the Evagrian lexicon, this word has a dual nature, one healthy and advancing of development and the other negative and morally stultifying.

The straightforward translation of this word is something like “self-love” or “love of self,” but in its negative connotation this term means something more like “self-obsession.” It’s a kind of inwardly possessed narcissism or solipsism cut off from the well-being of other people, the world, and, of course, God.

In other words, an over emphasis on our individuality will lead us astray.

This kind of self-obsession is rooted in pursuing good not for its own sake but for self-advancement and self-advantage. Gabriel Bunge describes this as “a state of being stuck in oneself that renders one incapable of love [agape].”

Its positive connotation refers to something more like self-compassion or care, epitomized by the less-well-known Greek imperative, “care of the self ” (epimeleia heautou), the compliment to gnothi seauton’s emphasis on knowledge and observation.

There is, then, in Evagrius a convergence of our knowing, caring, and attending, a relationship I’ve written about before, with each aspect of our “self” requiring different practices of development and redirection.

The dual methods of ascetical practice (praktikē) and contemplation (theōria) I outlined previously are in this way first rooted in the practice of nēpsis.

This type of paying attention is the center of the Evagrian psychology—a wildly nonmodern practice of self-examination that is also wildly appropriate for our times of being open to manipulation by subtle external forces, especially as we find them in our extended, mediated, and technological environments.

Perhaps a topic for another day.