I recently gave a talk at the opening evening of our newly founded event series, The Theōros Lectures, where I offered my views on the humanities, their history, and deeper purposes. These are my notes for the talk, along with the slide deck I used.

One of the main goals of this new initiative that we’re calling The Theōros Project is to meet head on the challenges of doing serious humanities work in the context of their institutional decline. My partner in this venture is Jacob Sherman, whom you should all be aware of if you aren’t already.

We are a small operation, but we’re also one of many groups now trying to create new places where deep thinking can happen, inside, outside, and alongside of the traditional institutional locations. I suspect these organizations will continue to grow and proliferate in the coming years—if not out of practical necessity, then out of a sheer appreciation for sharing this kind of work with people in general.

You can find a more philosophical introduction to our work here.

I’ll have more to say about all of this soon, but for now: This essay provides some data and background for why we should be thinking about the humanities in new ways. Portions of this talk come by way of an expansion—and, I think, a deepening—of a thesis I started working out in this earlier post, but there’s quite a lot of new material here as well, so do read on, even if you find some of the sections familiar.

A few of the main ideas you’ll find in this essay:

The historical evolution of the humanities, including their earlier incarnations in notions of paideia and studia humanitatis

Current challenges facing the humanities, such as declining enrollment, and an exploration of their value beyond transferable skills like “critical thinking”

The limitations of reducing the humanities to critical thinking skills, which fails to capture their true contribution to human beings and society

An alternative framework that views the humanities as rooted in practices of contemplation and transformation, connecting us to larger orders of reality

The importance of defending the humanities on these terms to understand their full significance in the twenty-first century

If you’re in or near the San Francisco Bay Area, I recommend signing up for our email list to receive news about future events in November, December, and January. All events are live and in person. We’d love to see you there.

The Humanities in History

Thank you all for coming. It’s great to see so many familiar faces show up to help us think through this new project of ours.

Much of what we want to share with you tonight is actually contained in our name The Theōros Project: Contemplation and the humanities in the 21st century.

But before we get to that I think we need to take a step back and look at a few of the pieces that are coming together to form our present situation as humanities scholars.

To do that, I want to first give a bit of context for the humanities and their history before looking at the current state of the humanities, paying special attention to the so-called crises that we’re facing.

Then, I’ll look at one common defense of the humanities that we’re hearing today in response to this situation: This idea that the humanities are valuable to us because they provide us with something called transferable skills—an approach I think is wrongheaded for reasons I’ll explain.

That’ll put me in a place where I can describe our perspective on the humanities—that is, the humanities as grounded in practices of transformation and what these mean for the value of the humanities as a whole, especially in relation to scholarship and this notion of theoria or contemplation.

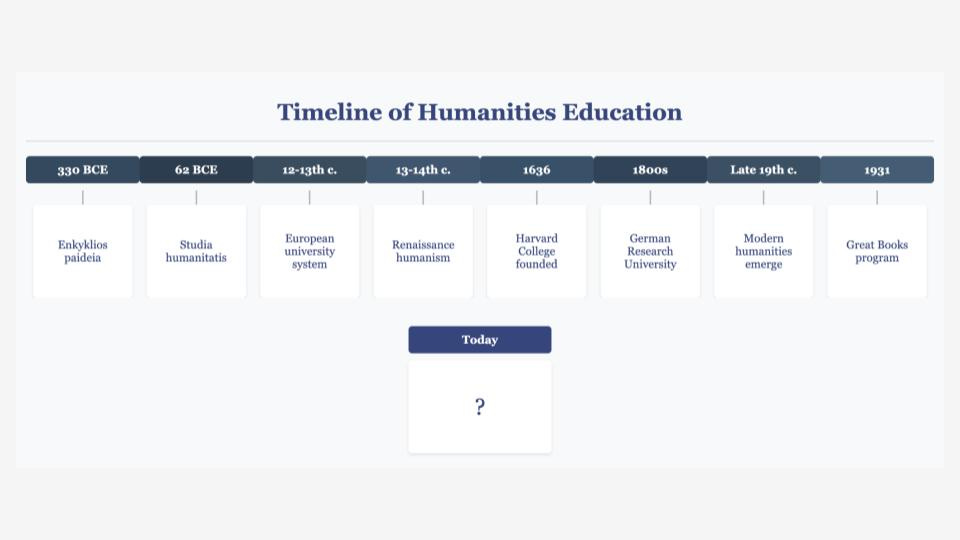

As many of you know this label “the humanities” as a term has a fairly recent origin, but before that it went under various monikers such studia humanitatis, in its Latin guise, and under paideia, or even enkyklios paideia, in its Greek rendering.

Both courses of study included an overlapping list of disciplines, though with some variation. Paideia comprised gymnastics, grammar, rhetoric, music, mathematics, geography, natural history, and philosophy. The studia humanitatis included grammar, rhetoric, poetry, history, moral philosophy, and ancient Greek and Latin studies.

The precise list of disciplines included in “the humanities” today has shifted somewhat over that time, but when we refer to the humanities, we’re talking about something like the following: we’re talking about classics, literature, philosophy, history, languages, but also art, music, poetry, religion, spirituality, and theology.

Regardless of the name that you give it, or the exact disciplines included within it, this is more or less what we’re talking about when we’re talking about the humanities.

There is a standard history of paideia and studia humanitatis, moving through into the European university system, the German research university, the modern Humanities, and so on that we’ll return to throughout our discussion, but for now what I want to do here is simply signal that there is a point of concentration in our efforts at education that have a touch point in something called paideia, and that we are still today pulling on that same thread, however varied that pulling might have become.

As you can see, the humanities (paideia, studia humanitatis) existed for a full 1500 years or so before the university system came in to being. My view, my bet to all of you, is that just as there’s been this 1500-year period where the humanities developed before being incorporated into universities, there’ll be a new chapter after the universities as well. Their future is uncertain, and they’ll likely evolve rather than disappear, but the role of the humanities in this future system is a bit uncertain right now, as we’ll see.

My sense is that the structure of the humanities is going to take a new form—and already is, in some some cases—just as they’ve done many times throughout history. And so that’s part of what we want to think about today. What does that next box look like? What are the opportunities in the face of this crisis that we’re up against? Our challenge is to anticipate and prepare for these impending changes. I’m hoping we can pick up on this point in our discussion after these presentations.

A future historian, I would say, would look—maybe not at this year in particular, or even at this decade, but maybe this century—they’re going to look back and see a new one of those boxes filled out in that future timeline. There’s going to be another box over there where this whole program takes a new shape. That’s part of what we want to think about, but I want to start from our current situation.

My view as I said is that we’re currently in new territory when it comes to this story, and part of what we want to think about together tonight is the potential new shapes the humanities might take in the twenty-first century.

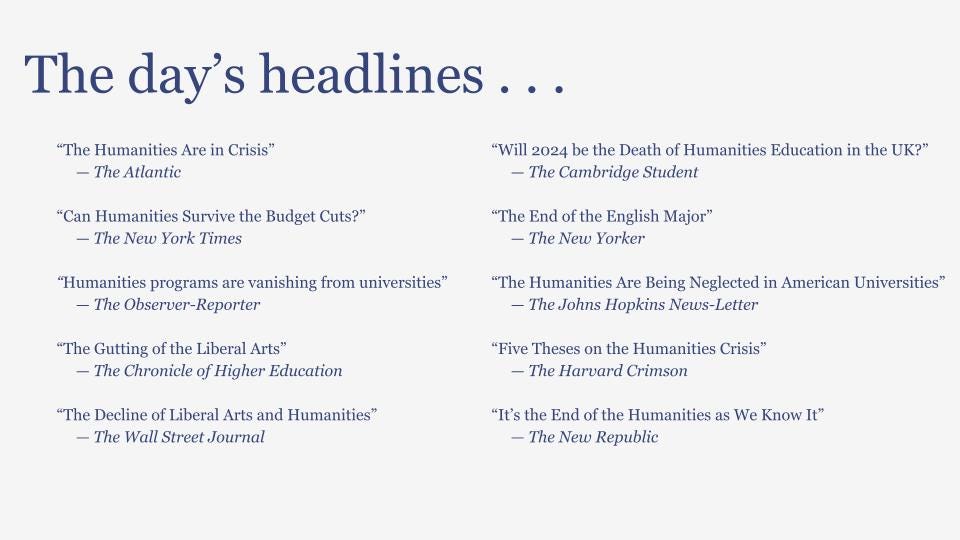

But, as you all know, the humanities are frequently in the headlines today, and the news isn’t great. You see “The humanities are in crisis,” “Can they survive the budget cuts,” “Gutting the liberal arts,” “That’s the end of the humanities as we know it,” and so on. It’s not a very positive moment.

I’m going to look at some numbers here, and then we’ll get to the philosophy, but the numbers are important, too.

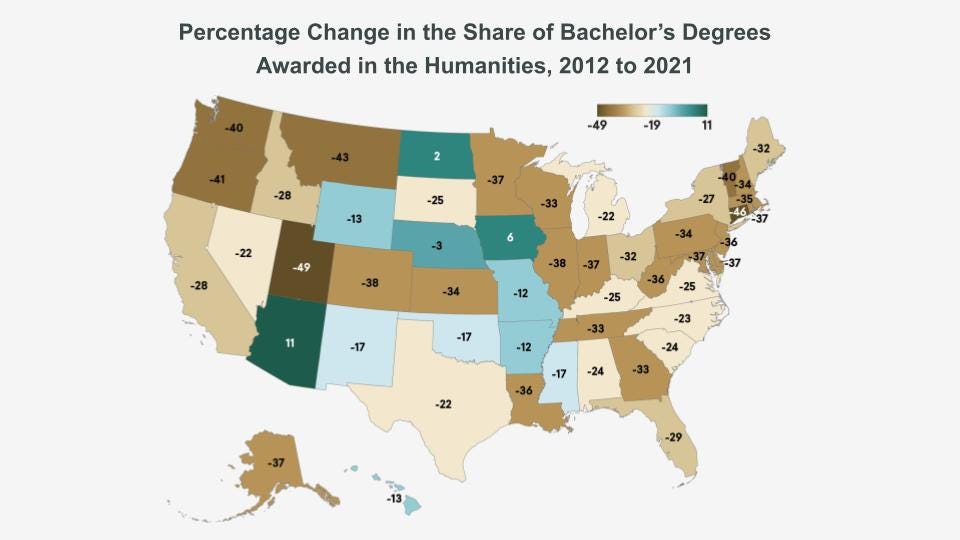

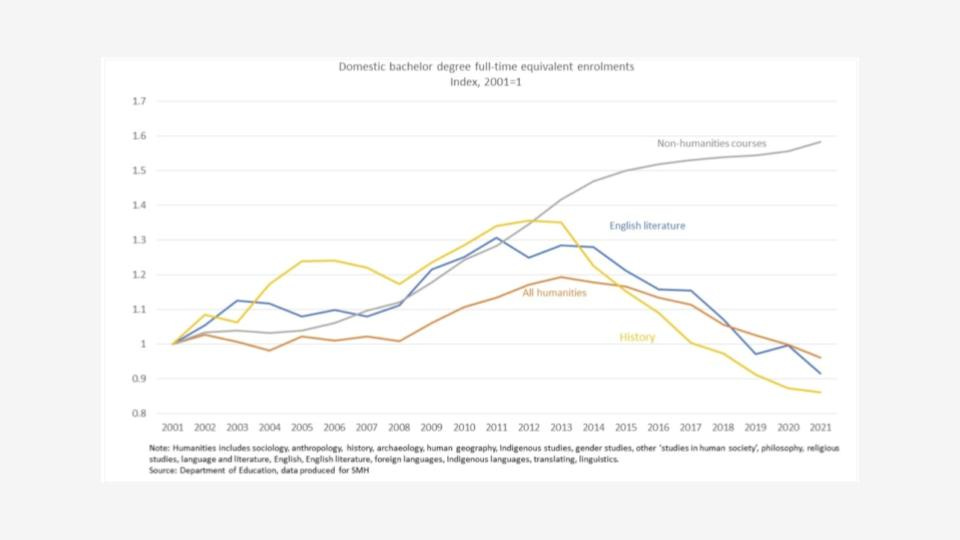

You can see that there’s a steady downward trend basically across the board in all of the humanities. We were peaking around 2008, and now it’s on this downward trajectory, after the financial crisis. And this is true basically across the whole country. If you look internationally, it’s a problem internationally as well. But if you just stick to our country, the United States, you can see that this is happening in basically every state—red, blue, East, West, everywhere, with only a few exceptions.

Interestingly, the number of people who are getting bachelor’s degrees in the humanities is going down, but the number of people who are going to college is going up. We actually have more college students today than we’ve ever had in history. There’s more programs, there’s more students, there’s more degrees. It’s just that while the humanities are going down, these non-humanities courses are going up.

So, in that context, we see a lot of people coming to the defense of the humanities, saying, “Okay, how can we get people back into these programs?” People are going to college, but they’re not taking these courses. We think these courses are important, but they’re not showing up as a viable option in these discussions.

The decline here is evident, and there are many people and groups out there making the case for why we need the humanities. This is where this defensive posture starts to take shape. People start to think of ways they can justify a humanities degree.

The Transferable Skills Defense

So let’s look at one common response—that the humanities teach valuable transferable skills. This view says you may not take your specific background with you into the workplace, but the way it taught you how to think will help you economically.

You’re not going to take your English degree or your history degree or your philosophy degree into the workplace in terms of the substance of that degree, but there’s something that does carry over. There’s some important skills there.

I know that the defense given for my discipline, philosophy, often comes in this predictable size and shape. The most common answer I hear is that philosophy teaches something called “critical thinking.”

This is the transferable skill that philosophy offers, we’re told, and this skill, in terms of competing for jobs, is central to this account of what the humanities help us do. And we do have data indicating that humanities degree holders on average earn about 40% more than non-degree holders, so there’s an economic argument here.

In some respects, this is a clear, legible answer. Jobs are good!

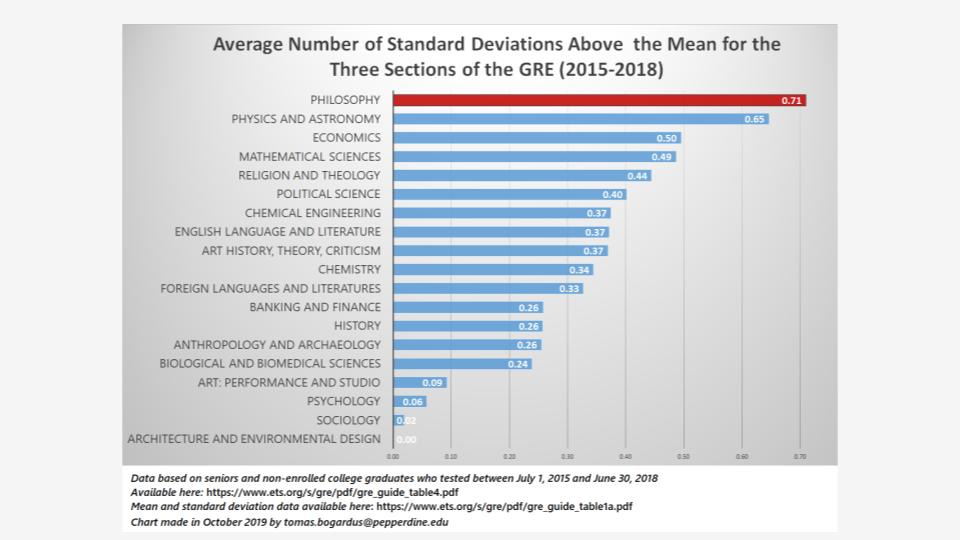

But in terms of learning these skills, we can see the numbers also back this up: Philosophers can, indeed, be very good at an abstract skill like “critical thinking.”

For example, in the USA, philosophers as a whole score the highest on the Graduate Record Exam (GRE), beating out physicists, astronomers, economists, and mathematicians. They also score highly on the LSAT and GMAT, and even the MCAT. (After the presentation, I came across this study [N = 122,352], that further corroborates many of these same results.)

This ranking certainly suggests a heightened capacity for something very general like “critical thinking,” and this capacity transfers into a valuable set of work skills.

So there’s this incentive structure. There’s an incentive structure set up, and then there’s these tests that demonstrate one’s ability to perform along this particular set of incentives. So people are thinking about this problem in terms of how can you compete in the incentive structure and how can you perform well on those tests. And we’re doing it—we’re competing in that incentive structure.

Hence this line of defense.

In this sense, the critical thinking defense kind of works, but this isn’t what we want out of philosophy. This isn’t what we want out of the humanities.

And what does critical thinking even mean? And is this, in the final analysis, what the humanities in general, and philosophy in particular, offer in the main to society?

I don’t think so. I’ll explain what I mean in a moment.

But first we have to confront the fact that in the culture at large we are faced with a narrowing conception of what philosophy is versus what it can be, and has been, at various times and places in history.

In a philosophical context, this kind of thinking that we’re testing so well on would be called thinking as dianoia.

This is thinking as discursive, syllogistic reasoning.

And to a certain extent, it’s an even further reduction than just thinking to dianoia, because this dianoia itself, this discursive reasoning, is being reduced to economic calculation, to utilitarian advantage.

Dianoia can be used for other things—like moral reasoning, for example.

So it’s a reduction of philosophy to dianoia, and then dianoia reduced to this kind of economic calculus. Today, I’d argue, the public tends to think of philosophy as critical thinking and critical thinking as this mode of discursive thinking or dianoia alone.

This isn’t a wrong characterization of philosophy, but this is simply a reduction of thinking to dianoia, as though the one exhausts the other, when thinking can and does mean so much more.

It’s for this reason that I think we need a stronger defense.

What does that defense look like? Well, historically, philosophers have employed modes of thinking beyond discursive reasoning—among them we can point to theoria (contemplation), phronesis (practical wisdom), and poiesis (creation, as in our poetry), but they also include other capacities like phenomenology, analogical thinking, meditation, and intuition, to say nothing of the wider range of practices grouped under the heading of askēsis, or spiritual exercise.

These are exercises that a person takes upon themselves in order to transform themselves. In transforming themselves, they learn to perceive differently, they learn to attend differently, they learn to relate differently. The world shows up differently through these practices, and that’s completely missing from this account.

This is the type of philosophy that Pierre Hadot argues for so eloquently. It’s about transforming the self through practice, and in so doing transforming our perceiving, attending, and acting in the world—drawing reason and practice together.

So the problem with this characterization of philosophy as critical thinking, then, is that it’s a narrow and partial view of what philosophy is and does, and even of what thinking is and does.

But it gets even worse because I don’t think that this is the aspect of philosophy that makes it distinguishable from other disciplines. This is an argument that a fellow named Eric Adler has been making recently, and I think his point is well taken here.

This appeal to critical thinking is thus further misguided because it’s likely not even the aspect of philosophy that makes it unique. If you think about it for a moment, other disciplines—e.g., law, engineering, physics, and economics—must also teach thinking in precisely this way in order for them to be effective.

Philosophers may be good at critical thinking, but they are not unique in deploying it.

Critical thinking is a transferable skill because it’s also the type of thinking already used in other disciplines and vocations.

That’s why it transfers.

Therefore, I don’t think this is the best defense of the humanities because these skills aren’t necessarily unique to our disciplines, and so why would we need the humanities per se to teach them? This defense sets us up for failure.

So, let’s look now at our alternative characterization, one that I think gives a fuller defense of the humanities on their own terms, one centered on these practices or stances of transformative and expressive activity.

Contemplation and Scholarship

We often view the scholar as a person dedicated to knowledge acquisition of some kind, or as an expert in this or that field of inquiry. This isn’t wrong, exactly, but this definition doesn’t get to the heart of the matter, either.

I am taken by Simone Weil’s idea that scholarship, like prayer or meditation, is a way of training attention. A scholar, in this sense, is something like a contemplative, a scholar–practitioner, we could say.

We can take this idea one step further, as Weil does, and say that the exercises of education can be thought of sacramentally, as implements that transform our attention. I don’t mean this in the sense that we have something over here, called contemplation, and another thing over here, called scholarship.

What I want to say is that if we actually really pay attention to scholarship, if we’re actually present to what we’re doing when we’re doing scholarship, if we attend to and open up the phenomenology of scholarship itself, we find that contemplation is actually right at its center. In its most important moments, in its most lucid moments, in its most articulate moments, contemplation is already there.

What does that mean?

Well, contemplation means to “mark out a space for observation” or “to gaze attentively.” It’s about creating a clearing. You’re creating a clearing. It’s not thinking; it’s creating a clearing for thinking. Thinking happens, but in a space, in this clearing.

This is something like what contemplation looks like.

Moreover, the suffix “templum” in the word is the same as in the word “temple,” which in a more literal and concrete way also “marks out a space for observation,” as one might find in a monastery, retreat center, or library.

The word scholar contains a similar double meaning.

The Greek skohlē also notes a mode of “holding back, a keeping clear” but also a physical building for learning—the school or academy—much as the Latin schola marks a “meeting place for teachers and students.” The school is the same kind of physical affordance structure for this thing that we call contemplation.

It’s an externalization of the same phenomenon, and it’s also a place where the teachers and the students and the community can meet. There’s something about the conviviality of the exchange that’s important—friendship, community, contemplation all coming together in one act of deeper interpersonal engagement.

In other words, the contemplative and the scholar—seen here as one person—are in the business of creating spaces for openness and receptivity, spaces that give way to the creative work of insight and inspiration and grace.

Contemplation in this sense is going beyond the sort of inward-facing introspective subject that we’re familiar with when we think of “contemplation” or even “meditation.” It’s a thing that puts us in touch with the world “out there” but that we don’t always attend to. I like drawing from another Simone here, not Simone Weil but Simone Kotva, and she’s done a lot of thinking on spiritual exercises, on philosophy, and on contemplation, and on this kind of shift that I’m talking about here.

This shift points to something missing, something that’s not there in the more active, intellective, critical mode of thinking that we were just talking about.

On this different approach to philosophy, Kotva says, “Receive is the key word here for what spiritual exercise, as distinct from human effort, draws attention to is the significance, for wisdom, of a style of thinking and doing that is different from effort and yet not separate from it. A style of thinking and doing that the handbooks of spiritual exercise would call ‘receptive’ and would associate, closely, with the experience of intuition, inspiration, illumination, and other ‘passive’ modes of knowing distinct from the ‘active’ modes associated with reason and intellect.”

The Humanities as Pathways to Deeper Being

So if we think in this sense about the great works of art or poetry, literature, philosophy, theology, and so on, these are texts or artifacts, but they’re also opportunities for transformation, agencies to engage with that reconnect us with these larger or more subtle orders of being, or to moments in time where new, more delicate things can unfold. In a sense, we are both a part and an expression of that unfolding, and so we’re also a folding back on it, and we’re giving voice to it, through these disciplines of expression and communication.

In other words, part of what good humanities training is doing is not just giving you this more receptive attunement to reality, to being, but we’re also getting skills to articulate it and communicate it and talk about it.

That’s what we’re doing tonight—we’re talking about what we think is happening in these situations, and how the humanities may help us enable it. I’ll share with you one more quote that gets at the same thing.

This is Josef Pieper. He says, “In the tradition of which I’m speaking, the philosophical act is a fundamental relation to reality, a full personal attitude which is by no manner of means at the sole disposal of the ratio. It is an attitude which presupposes silence, a contemplative attention to things in which man begins to see how worthy of veneration they really are.”

We have here an interesting association of terms, some related terms.

We have contemplation, but we also have reverence and wisdom, rather than knowledge alone. We have silence, we have attention, we have veneration, taken together now with these earlier ideas I mentioned about conviviality and community and clearings for thinking. There’s also this sense that these connections are deeply personal, they’re about you as a unique perspective on the whole of things.

The point is, these attitudes or dispositions shouldn’t be thought of as decorations around the more primary activity of reason, but as actual epistemic catalysts that transform our own being, and so our own perception, of that larger being of which we are a part. Silent veneration is an epistemological activity as much as it as an emotional or aesthetic stance on things. They all come together.

And in that type of prepared clearing all kinds of new phenomena may appear.

I’m saying that these are attitudes and practices that are crucial to this enterprise that we call the humanities or that I think of as essential to philosophy. This gives us a different avenue from which we might talk about the humanities, as consisting in practices of attention and transformation that modify not just who we are as persons, but how we engage with and render this larger being of which we are a part.

A few people might respond that this isn’t an appropriate task for the humanities—this business of telling us about reality as it is in itself. For instance, they might argue:

The sciences are here to tell us about how real things work outside of the human domain (in cosmology, physics, chemistry, etc.), while the humanities are important insofar as they tell us about the human condition from the perspective of human beings. This is also a true story—the sciences do tell us about the more-than-human world and the humanities do tell us about the human one—but the more radical perspective I’m putting forth here is that the humanities also tell us about the more-than-human world in ways the sciences don’t, as for example in the disciplines of literature, myth, metaphysics, or theology.

In this context, Jeffrey Kripal, I think, really gets at what I’m trying to say. He says, “I mean to argue that religious ideas and symbolic expressions might sometimes function . . . as imaginative cultural translations of actual human encounters with consciousness and the cosmos, including aspects that no scientific mode of knowing can touch for one simple but profound reason: because they are not things or objects to touch, much less measure and manipulate.”

Now, as I’ve said, we moderns tend to think of theoria (contemplation) as an inward and individual practice but it shouldn’t be understood in such limited terms.

Indeed, the practice of theoria is in many ways the opposite: It’s an opening out upon and toward reality—to being in its broadest sense.

The other disciplines, no matter how valuable, simply don’t do this. And when they do, well, they’ve veered back into the landscape of the humanistic disciplines, and these disciplines deserve defending on their own terms, rather than as handmaids to other programs or as actions limited to the human sphere alone.

I’ll leave you one more quote from Jeffrey Kripal before turning it over to Jake that I think really gets at our attitude towards the humanities: “I think the humanities are so important because the humanities are really the superhumanities. I think there is something cosmic or superhuman smoldering in the human, something that seems ever ready to burst into flames, and sometimes does. A few fortunate souls intuit this superhuman smoldering in particularly inspired books, themselves about to burst into flames—yes, books, of all things—and decide to give their lives to the pursuit and nurturing of that, whatever ‘that’ is.”

“We were cosmic, it turns out, before we were human. Way before.”

So I think this points us in a better direction. This gives us a better—if you don’t want to think of it as a defense, you can think of it as a proactive description—of what the humanities are, these practices of transformation that attune us to reality and to each other in a way where we also come out the other side more able to articulate these relations that we’re put in touch with.

The humanities are engaged in this self-transformative project of relating ourselves to each other and to being in deeper and more interesting ways, and I think that’s what we’re after here. Through practices of attention and contemplation, through literature, philosophy, and theology, the humanities offer us ways to engage with reality that go beyond what the sciences can measure or manipulate.

In this light, the humanities aren’t just academic disciplines that engage us in something like critical thinking. They are articulate pathways to transformation—practices of perception and attention—that allow us to open out toward reality in its broadest sense and to speak meaningfully, and even rationally in that dianoetic sense I mentioned earlier, about these encounters.

This is what the humanities are about, ultimately, a developmental program for the human being—a paideia—that lets us go beyond the human being, crossing over into the metaphysical substrate that animates us and from which we come and to which we shall return. There is an art to speaking about this process of transformation, and the humanities are essential to enabling and then communicating that process and its importance for us as twenty-first century humans, and perhaps to helping us discover that it even exists in the first place. This is, I think, a better defense.

And while it may be the case that humanities programs will continue to fold inside the university system of today, I have no doubt that they will find new life and new form well into the twenty-first century. They’ve been through worse.

Thank you.

Adam, there is so much to think about in this talk or essay. Thank you. I like especially your articulation of the humanities as “pathways to transformation—practices of perception and attention.” I think we are all victims of aesthetic injustice, the damaging of our abilities to feel, imagine, and perceive by governments, religions, economic systems, and others. One of the most important values of the humanities is their ability to offer an antidote by presenting a diversity of ideas, images, and perspectives that can expand and inspire our imaginations, feelings, and perceptions. This is one important way the humanities are transformative.

Gustavo H. Delaqua’s article, Aesthetic Injustice, originally published in the Journal of Aesthetics & Culture. 2020, Vol. 12, issue 1, https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/20004214.2020.1712183, offers insight into how the humanities can respond to injustice.

Though the humanities are often disvalued and seen at best as entertainment, it seems that under totalitarian governments artists, writers, poets, song writers, playwrights, historians, philosophers, and other practitioners of the humanities are among the first to be silenced, arrested, exiled, or disappeared. To get this kind of attention, they must be offering something more than transferable skills.

Excellent, thoughtful, clear, compelling, and certainly appropriate for these times. I'd add that if you take a look at Evan Thompson's Blind Spot, current cog sci, and even consider the ideas of Michael Levin, the biologist, who is describing life itself, as the ability of an "organism" to take a perspective, the role of the human and their perceptions matters very, very much to science. Thus, refining, shaping, and sharpening ourselves through contemplation and practices, may possibly be a biological and evolutionary necessity, and possibly necessary to the continuation and enhancement of the hard sciences themself. I know you don't go this far here, likely wisely, but I think it is a very real likelihood the humanities as you characterize them are fundamental to all human endeavors. Thanks for your work.