Apologetics for Philosophy

And what do we defend when we defend the humanities?

The humanities must be defended.

We hear this kind of thing all the time, and some of us, myself included, feel inclined to do the defending.

But what are we really defending? And are any of the common responses any good?

It’s worth thinking about.

I want to look at two common responses in this essay—first, that the humanities teach valuable transferable skills, and second, that the humanities put us in touch with tradition—not to discount them, but to complement them with a third view: The humanities are worth defending because they put us in touch with reality in new, old, and timeless ways, ways unique to the humanistic disciplines.

I’ll start with the first two responses and then conclude with the third.

As always, if you enjoy The Base Camp, consider forwarding this email to your friends and colleagues, or just share this link with your networks.

Critical Thinking as a Defense

The first response says that the humanities are worth defending because they teach transferable skills, useful in a number of vocations, and thus they’re good for the job market. You may not take your specific background with you into the workplace, but the way it taught you how to think will help you economically, goes the story.

I can’t speak for the liberal arts as a whole, but I know that the defense given for my discipline, philosophy, often comes in this predictable size and shape. The most common answer I hear is that philosophy teaches something called “critical thinking.”

This is the transferable skill that philosophy offers, we’re told, and this skill, in terms of competing for jobs, is central on this account of what the humanities help us do.

In some respects, this is a clear, legible answer. Jobs are good!

And the data back it up. In the USA, philosophers as a whole score the highest on the Graduate Record Exam (GRE), beating out physicists, astronomers, economists, and mathematicians. They also score highly on the LSAT and GMAT, and even the MCAT.

If you look at the GRE results in particular, we find that philosophers score highly on this exam not because they do exceptionally well in any one of the test’s three categories (analytical writing, verbal reasoning, and quantitative reasoning), but because they achieve higher scores on average in all three domains. When taken together this results in their higher position overall.

This ranking certainly suggests a heightened capacity for something very general like “critical thinking,” and this capacity transfers into a valuable set of work skills.

Hence this line of defense.

But what does critical thinking even mean? And is this, in the final analysis, what the humanities in general, and philosophy in particular, offer in the main to society?

I don’t think so. I’ll explain what I mean in a moment.

But first we have to confront the fact that in the culture at large we are faced with a narrowing conception of what philosophy is versus what it can be, and has been, at various times and places in history.

So what is critical thinking? And is it philosophy?

Critical thinking ends up being adjacent to a variety of related skills, including logical reasoning, problem solving, and abstract conceptualization, on some accounts, or evaluating propositions, making arguments, and linguistic analysis, on others.

All of these skills pre-suppose that you can take a step back from a claim or a narrative and observe the way that both are constructed and whether or not that construction is legitimate from a rational perspective.

This is the key first move of critical thinking, stepping back; it’s a kind of suspension of belief, an epoché, to use a term of art. If you are a good communicator, then you can also put this process on display for other people. This is another move—you’re stepping back and then stepping back in with a different view.

If you want a visual metaphor, critical thinking gives you the capacity to create exploded diagrams of our taken-for-granted concepts and assumptions. This is probably why philosophers are often encouraged to become lawyers—you’re getting inside of these arguments and perspectives like a conceptual mechanic. You can open them up from the inside and tool around with them. At some point, you may even create your own concepts that other people can put to use (and other people can take those apart, and so on). This means it’s also a kind of creative thinking.

Critical and creative thinking thus presuppose the same root ability of working in the medium of concepts and language, at least analytically, if not artistically, as well.

Thinking Beyond Critical Thinking

In any case, it’s fair to say that critical thinking in all of these forms is bound up with a more general kind of thinking called representational thinking. In a philosophical context, this kind of thinking would be called thinking as dianoia.

This is thinking as discursive, syllogistic reasoning. And here we’re starting to get at something important about philosophy—it is, even at this level, already a kind of thinking about our thinking. It’s thought that takes thought as its object.

In other words, this kind of thinking is about making or evaluating arguments and premises through the construction of representations (i.e., with words and symbols, including language, math, or code) towards some aim, often instrumental in character (hence the appeal in the workplace).

Today, we tend to think of philosophy as critical thinking, critical thinking as representational thinking, and representational thinking as this activity called dianoia.

This isn’t a wrong characterization of philosophy, and as I noted above, there is good evidence that this type of thinking is an activity that trained philosophers have above-average ability in performing. Good for us.

But this is simply a reduction of thinking to dianoia, as though the one exhausts the other, when thinking can and does mean so much more.

Historically, philosophers have employed modes of thinking beyond discursive reasoning—among them are Greek descriptors of thought like theoria (contemplation), phronesis (practical wisdom), and poiesis (creation, as in our poetry), but they also include other capacities like analogical thinking, meditation, intuition, and aesthetics, to say nothing of the wider range of practices grouped under the heading of askēsis, or exercise. These modes of thinking, often intertwining, allow philosophers to engage with a fuller spectrum of human experience and reality than dianoia alone allows.

The problem with this characterization of philosophy, then, is that it’s a narrow and partial view of what philosophy is and does, and of what thinking is and does.

Moreover, it’s likely not even the aspect of philosophy that makes it unique.

If you think about it for a moment, other disciplines—e.g., law, engineering, physics, biology, chemistry, architecture, and coding—must also teach thinking in precisely this way in order for them to be effective.

Philosophers may be good at critical thinking, but they are not unique in deploying it.

Critical thinking is a transferable skill because it’s also the type of thinking already used in other disciplines.

That’s why it transfers.

Touching Greatness and Reality

Another version of the humanities defense will tell you a true story about history and tradition, connecting the humanities today to their predecessors in Ancient Greece, Latin Rome, the Italian Renaissance, the European university system, and so on. To access that history, you need able guides and translators—people who can carry this tradition forward and share with the rest of us the insights that abound within it.

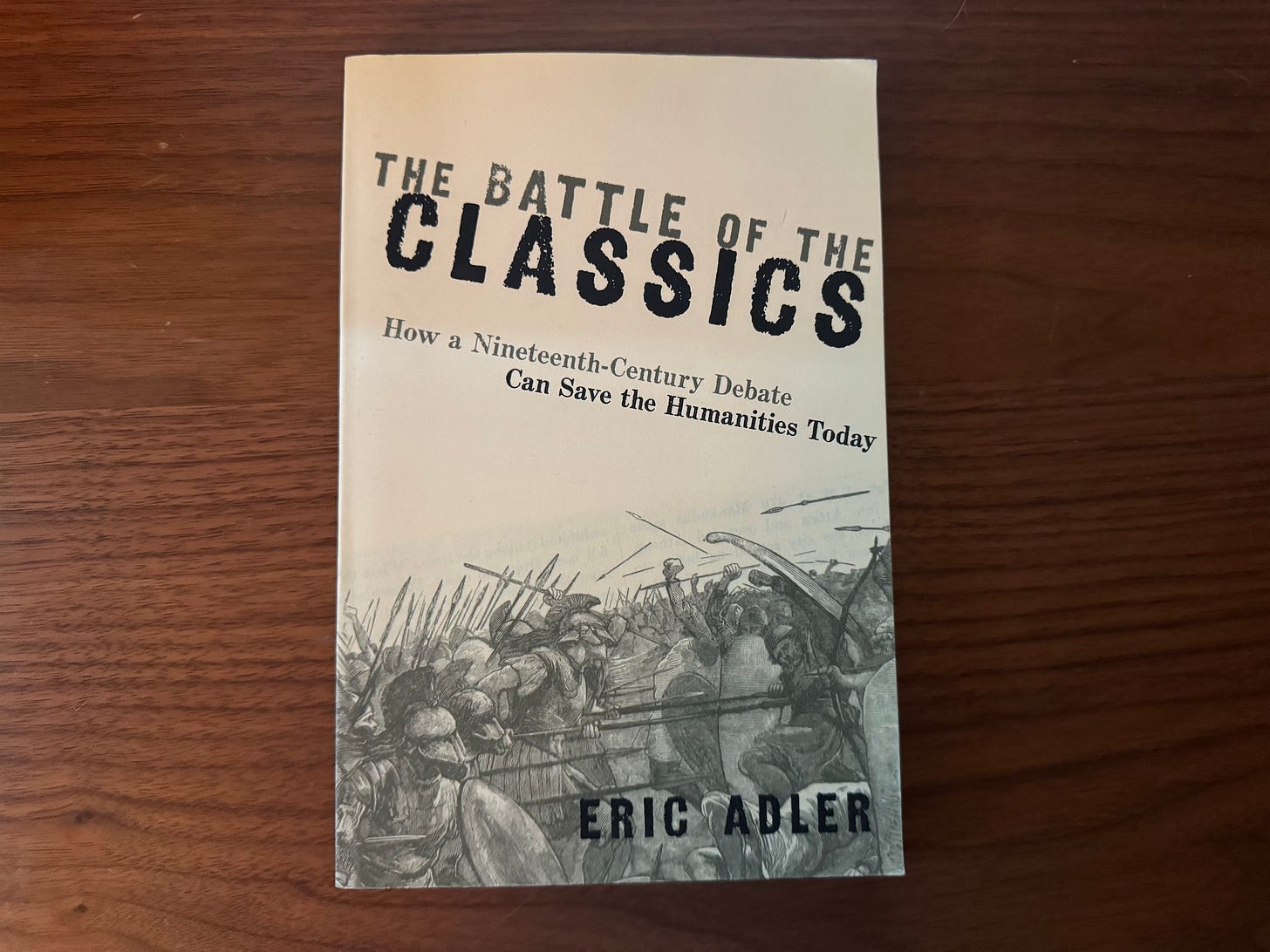

This is one way of summarizing Eric Adler’s argument for why we should study the humanities. For Adler, the value of humanistic scholarship to the general public isn’t found in a set of transferable skills, but in a set of substantive ones related to this proximity to and facility with the great texts and works of art of human history, including texts and works from civilizations the world over.

The humanities on this account are not important because they train people in some set of transferable skills—such as critical thinking, deep reflecting, or sophisticated writing (though these skills may result)—but because they preserve and expose us to the great achievements of human beings across time and place.

On this view, it is making available a proximity to this greatness that matters to humanists, and not some smaller subset set of utilitarian skills one may acquire in the course of a degree program, though as we saw earlier these skills are, in fact, obtained.

Humanists are important because they are stewards of tradition, this argument goes.

Now, both of these defenses—that the humanities teach valuable transferable skills and that they put us in touch with tradition—are just fine as far as they go, but they miss a crucial further element of what the humanities do, and must continue to do, and that is, interestingly enough, that they do more than get us in touch with being a human and our human history.

That’s only part of it.

The other part is that they get us in touch with the reality of which we humans are an integral component. In other words, I’m arguing for a view of the humanities that sees them as deepening and enlivening our relation with and attention to being, the whole. In this sense, the great works of art, poetry, literature, philosophy, and theology throughout history reconnect us to the larger orders and higher times of which we are a part and an expression.

So in what, exactly, does this greatness consist? A few things come to mind.

An astonishing capacity to render the human condition, to be sure, but also the giving of an opening to the greater being that surrounds us all, and in which our lives inextricably participate. Proximity to greatness, proximity to ideas, proximity to practices, and most importantly, to what these practices put you in contact with in terms of how they disclose reality in different ways, are what the humanities offer.

These contributions are not in competition with reason or critical thinking. Reason is a crucial piece in this image of philosophy. Rather, this is a view of philosophy that includes a greater ambit of practices than what reason alone can provide and that tend to and attune us with a wider range of faculties than reason by itself can understand.

The answer to the question why study philosophy? is then that getting in touch with this archive of greatness will put you in touch with practices and insights that in turn put you back in touch with reality, with being, in new, old, and timeless ways.

And they do so in a way that lets us glean what reality is in a deeper sense.

A few people might respond that this isn’t an appropriate task for the humanities—this business of telling us about reality as it is in itself. For instance, they might argue: The sciences are here to tell us about how real things work outside of the human domain (in cosmology, physics, chemistry, etc.), while the humanities are important insofar as they tell us about the human condition from the perspective of human beings.

This is also a true story—the sciences do tell us about the more-than-human world and the humanities do tell us about the human one—but the more radical perspective I’m putting forth here is that the humanities also tell us about the more-than-human world in ways the sciences don’t, as for example in the disciplines of literature, myth, metaphysics, or theology. But more than that, they tell us a story about the human world situated in this more expansive reality, whilst still holding a place for the integrity of the human being as an irreducible whole within this larger picture.

This view is similar to the argument Charles Taylor makes about poetry—that poetry doesn’t just tell us about human feelings and relationships, but gets us in touch with the larger orderings of being through the artistic use of symbolism and language.

Taylor offers us a good touch point for thinking about philosophy in the sense I’ve described above (i.e., as not limited to critical thinking). For example, we moderns tend to think of theoria (contemplation) as an inward and individual practice but it shouldn’t be understood in such limited terms. Indeed, the practice of theoria is in many ways the opposite: It’s an opening out upon and toward reality—being in its broadest sense. Philosophy, then, like Taylor’s account of poetry, is about how we should understand this larger whole of which humans are a part but also how the whole and the individual come together, not just in theoretically coherent terms but in the light of practices that actually get us in touch with these relations and bring them to awareness—especially in normative terms about how we should live.

The other disciplines, no matter how valuable, simply don’t do this.

And when they do, well, they’ve veered back into the landscape of the humanistic disciplines, and these disciplines deserve defending on their own terms, rather than as handmaids to other human endeavors or as actions limited to the human sphere alone.

The humanities must be defended!

The humanities and mass democracy have never and will never go hand in hand down skipping down the lane.

The common man is not suited to philosophy nor has he ever had a true interest in it.

Philosophy is by and for an elite.

The best we can do is to recall the last few lines of Dover Beach.

This is a bit late to the war. You can't defend the humanities after they are already dead.

Don't you know they have only cared for math and science for the last century. The humanities died in the 1940s at the hands of the Robber Barron's of the 1920s/30s. When they opened the teacher's retirement fund to teachers who used their disgusting child conditioning curriculums.

Your should be writing to resurrect the humanities. Which is my goal. But the masses are so brainwashed. I had to start with marginalized and the young.

The older ones only scoff. Those idiots gave up their humanity for mass produced trinkets and there is no way to change that now.

You can't teach old dogs new tricks because they were conditioned so profoundly it destroyed the world.