Turning and Conversion

On Collective Practices of Transformation

Discussions of conversion experience—transformations in one's being, way of life, or religious orientation—often emphasize the "turning motion" (conversio, in Latin), emphasizing the action "to turn" (vertere).

The language of "turning around" isn't incidentally related to moments of conversion. It's central to them. You were pointed in one direction, and now another.

You've turned around to another point of view. The world has changed.

The Greek epistrophe also means to turn, but with an emphasis on turning towards, or turning back, a term contrasted with metanoia, which points to a spiritual conversion experience associated with transformation or rebirth.

These are different types of turning—turning towards, turning back, turning around. As Pierre Hadot says,

The Latin word conversio in fact corresponds to two Greek words with different meanings, on one hand epistrophe, which signifies change of orientation and implies the idea of a return (return to the origin, return to the self), on the other hand metanoia, which signifies change of mind, repentance, and implies the idea of a mutation and a rebirth. There is, then, in the notion of conversion, an internal opposition between the idea of a “return to the origin” and the idea of “rebirth.”

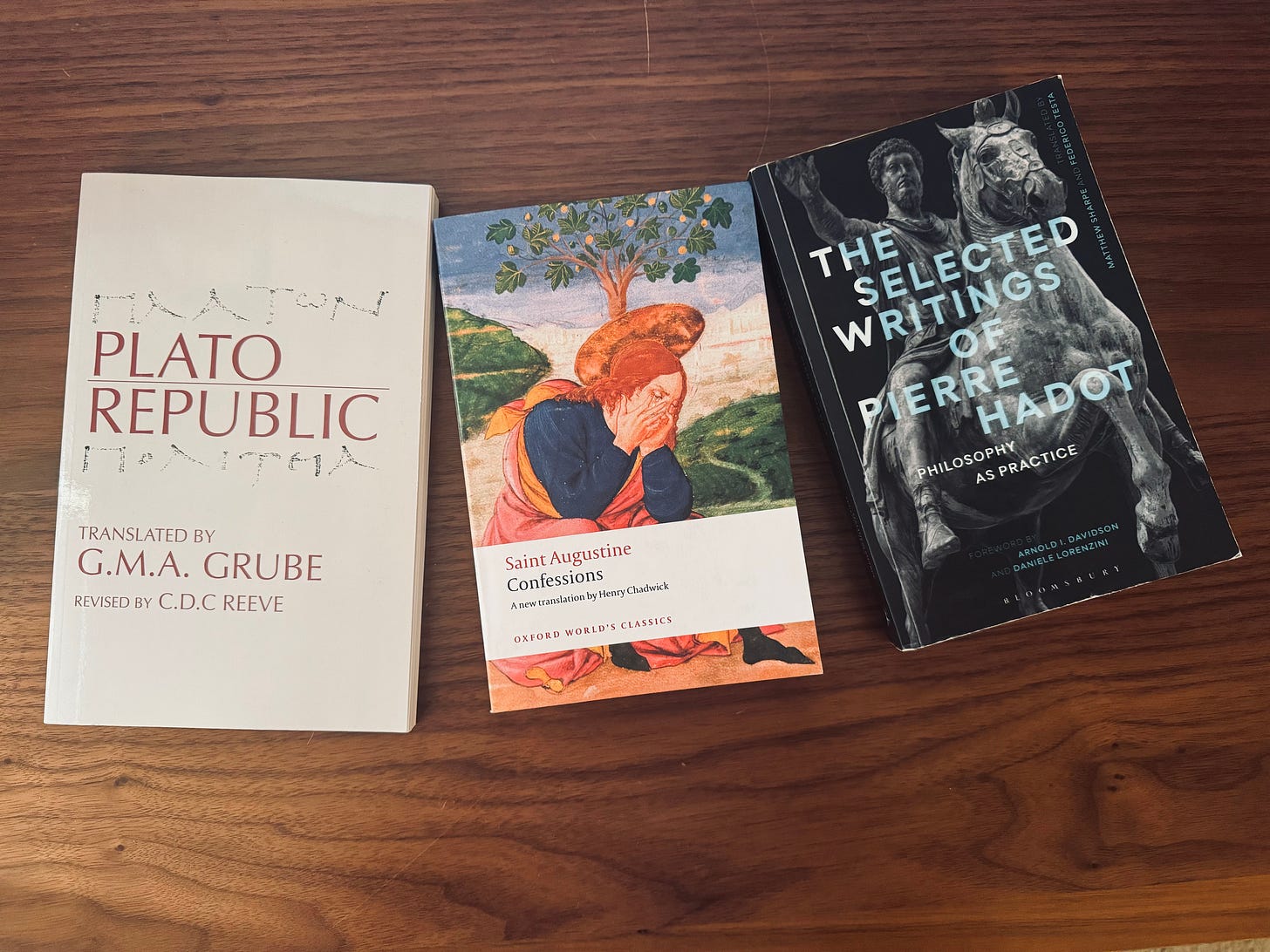

Plato also uses the term periogage to signal the movement that has the prisoner’s in his Allegory of the Cave “turn around,” away from the representations on the cave wall and begin their ascent upwards to the outside world. This turning motion, dramatized in Plato’s Republic (wherein we find the cave allegory), is in many ways the founding motion of philosophical training and education.

Indeed, the Greek enkyklios paideia—the method of “circular education,” envisioned as a “turning wheel” or a system of “training in a circle”—is at the basis of what we today call the liberal arts. Ilsetraut Hadot noted that the enkyklios paideia is both a circular structure and a movement, a cyclical activity (kyklos can mean both “circle” and “cycle”), suggesting a unity and completeness in this program of study.

In turn, a lack of paideia means no turning around, no conversion experience, no movement, and thus, no education (apadeuisia).

As important as these movements and distinctions are, lately I've come to think that the prefix "con-" (com), meaning "with" or "together" is underrepresented in these discussions. Conversion is not exactly self-transformation, as if the the self is an isolated entity, engaged in an individualistic pursuit of change.

As the name implies, the turning is always con-vertare, "turning with, or together." The togetherness of the turning can point to many things depending on the context. In other words, we always turn with specific friends, communities, places, and times and towards certain realities—God, the Good, the Sun, the Cosmos, and so on.

Pierre Hadot often uses the language of individual self-transformation when talking about conversion and the spiritual exercises (askēsis) that accompany it.

However, he’s well aware of this collective dimension as well.

He gives a number of examples. He says Platonic conversion is a political conversion, a transformation of the soul in the direction of a transformation of the city, the polis, achieved through the collective effort of education, the paideia.

The dialectic itself—real philosophical dialogue—requires sincere companionship, a movement of friends guiding one another to a conversion of thinking.

Likewise, Judaic and Christian experiences of conversion should be understood in the context of their respective religious and Church communities and their extended social histories. And for the Stoics, conversion is the movement of an interior Logos out into the animating Logos of the universe at large (and then back inward again).

In short, conversion involves turning towards or turning back, but it’s also always turning with, turning together, and this is as essential as the movement itself.