Thinking is Creating

A description of thinking, via negativa, using Henri Bergson’s account of memory and perception—a thinking enabled by ekstasis, theōria, and poēsis.

I have been giving increasing thought to memory these past few months. Initially, I explored the topic through the work of scholars like Francis Yates and Mary Carruthers; both of whom explore memory in the context of the history and practice of memorization and the role places and texts play in this work.

In these accounts, we find depictions of the art of memory in ancient mnemonic systems, in memory theaters, and in monastic and scholastic disciplines of shaping the soul through repetitive reading and writing practices (as we find in Lectio divina and elsewhere), all treated as means of training attention and contemplation.

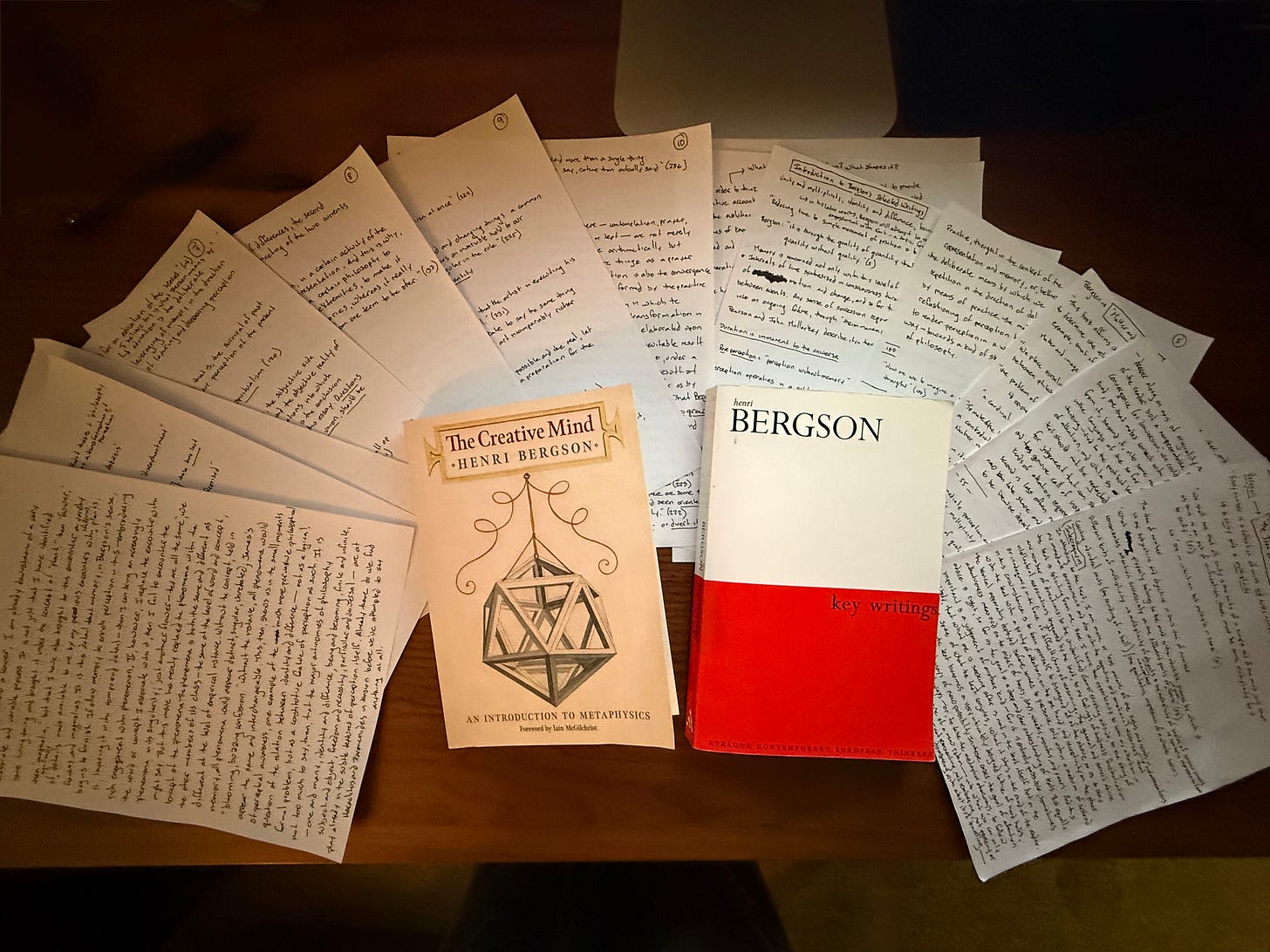

More recently, I’ve been drawn to Henri Bergson’s work on what we might call the metaphysics and phenomenology of memory and perception.

In this piece, a first sketch on Bergson, I draw him out on the relation between memory and perception, and the unique role that thought plays in this work. If we follow Bergson and accept the idea that all perception, even at its basic level of sensation, involves memory, then we should ask: What lies outside of these “memory-images”—Bergson’s term for how past experience endures within us, cooperating with present perception—and how do we step outside of this patterning?

My answer, argued for below, is thinking, which, if we accept my terms, ends up being a very rare activity indeed, one that we can’t identify with recall or representation alone. Instead, thinking must be something else—because if it were only recall or representation, it would merely repeat what is already known. Thinking must in some sense be a kind of interruption, one that I will argue has three characteristics: It is external (to repetition and memory), contemplative, and generative. I mean these in the sense of thinking as partaking in the movements of ekstasis, theōria, and poēsis, or in a kind of receptivity and creativity that stands outside the structure of repetition.

1. Memory and Perception

Bergson himself doesn’t provide a theory of thinking in this sense; what follows is my use of his framework to study, via negativa, the space in which such an account might emerge. To get there, we first need to understand how Bergson parses the field of memory itself. When Bergson turns his attention to memory, we find not a singular and undifferentiated field, but a multiplicity with distinctions, a taxonomy of different kinds of memory that hang together in different ways depending on our actions and circumstances. As this field comes into greater focus, details and differences emerge—a whole ecology of remembering.

Thus with Bergson we might identify memory as contraction (how the plurality of moments are synthesized into a unified whole), perception (how the content of experience is realized as meaningful in a basic semantic sense), habit (a non-representational physical response), recollection (memory as the representation of a past event), and pure (the totality of one’s past experiences as a whole). For a deeper exploration of these distinctions, I recommend this paper by Trevor Perri, who has done us all a great favor by drawing out these terms from across Bergson’s many works and showing how they, in the end, form a variegated but continuous whole.

For our present purposes, I am interested in memory in the first two senses—contraction and perception—since these are the ones most relevant to Bergson’s account of memory and sensation. As he says in Matter and Memory, “There is no perception which is not full of memories. With the immediate and present data of our senses, we mingle a thousand details out of our past experience.”

The implication of this view is that memory is both what secures the possibility of intelligible perception, on the one hand, and what establishes the habits that constrain perception to past encounters, on the other. When we read a statement like this one, we are tempted to see it as a commentary on our psychological profile—in other words, that we bring a personal history to our impressions, one that colors perception with its preferences, inclinations, and idiosyncratic histories.

This observation is true enough insofar as our perception of things is influenced by an individual past. But I do not think this level quite gets at Bergson’s meaning, or at least it is not limited to this level of individual psychology alone. It is not, in the main, a commentary on how our personal psychology projects meaning onto experience. Rather, I think the insight refers to a much smaller, more subtle, and more fleeting level of perception. With Bergson, we are at the interstice of memory and sensation, down to their root in the bringing‑to‑presence of objects, events, and causes as such.

Here we see Bergson as the philosopher of the very small—“the fugitive moment,” in his words—of the passing present, the interval of contact between perception and memory, arising and perishing in the flux of awareness. As Bergson says elsewhere, “We see in sensible qualities contractions effected by our memory.” If I see and behold a particular phenomenon—say, a flower—I am already for Bergson downstream of a very elaborate and variable process. It is not just that I have identified some living thing and brought it under the concept of “plant,” then “flower,” then, “magnolia,” but that I have also brought to this encounter a variety of meaningful details made available to me by my previous encounters with plants, flowers, and magnolias.

These details let me draw attention to the particularity of individual flowers whilst recognizing their standing in relation to other flowers, both of the same kind and beyond. This process is also what let’s us draw normative conclusions in our observations. We can say this plant is healthy, sick, in need of water or sunlight, et cetera, as a consequence of this comparative capacity born in memory.

It is precisely this detail and judgment that memory, in Bergson’s sense, begins to furnish. And it is because memory enriches perception in this way—embroidering it, layering it with compound detail—that I can bring an increasingly rich engagement to phenomena. We need only reinsert the missing hyphens in our terms to see how this works: we say re‑presentation, re‑collection, re‑cognition; all instances, in a sense, of re-petition. But these repetitions don’t just stand alone; they layer on top of one another in a cumulative fashion, in the same way one might layer paint onto a canvas to achieve a richer and more deliberate effect, except here the layers expand iteratively and retroactively within perception itself, as memory and sensation encounter phenomena again and again with increasing depth and detail. This is how perception learns and grows by accumulating experience into presence as we perceive.

For Bergson, this layering on of perception through memory is what “thickens,” so to speak, what we’re aware of when encountering the world. Memory in this way is concerned, first, with this level of recognition, but also, more generally, with the passage of time as such. The flowing intervals of time synthesized in consciousness through memory are what allow for our intelligible perception of motion and change, and so for the possibility of apprehending causal relations between events.

Any sense of succession requires a past synthesized with the present into an ongoing future in a continuous process. The past is still present inside the present, we might say. In their introduction to Bergson’s writing, Keith Ansell Pearson and John Mullarky describe this co‑presence as “the immanence of past and present” or “a virtual co‑existence of past and present.” This is part of what Bergson means by duration (durée)—time sensed not a series of discrete instants like points on a line, but a living flow in which past, present, and future interpenetrate. Duration is what lets time be felt as a continuum rather than a sequence of instances, and allows for its growth and deepening in and through experience, like we see in a living being.

2. Memory Overwritten

But this iterative process also carries a downside, depending on whether we emphasize the memory pole or the perception pole in our perceiving. Bergson posits two theoretical extremes: pure memory (memory without perception or content) and pure perception (perception without memory, a kind of absolute, unmediated encounter). These are hypothetical conditions more than concrete aspects of our experience—save perhaps for rare limit cases—but they provide a helpful way to imagine the continuum on which our ordinary experience sits.

But in the very act of enriching perception, memory also threatens to flatten it, overlaying the living moment with its stored templates of concepts and ideas. The risk of recalling the general concept over the particular instance is that I may replace the encounter with the word or concept I associate with it, and thus fail to encounter the phenomena in its singularity. “It’s just another flower; they are all the same,” we might say. This move has replaced the phenomena with the concept of the phenomena, and this is important because the phenomenon in question will be both the same and different to the other members of its class. It is the same at the level of word and concept, and different at the level of empirical instance.

Without the concept, held in memory, all phenomena would appear distinct, singular, unrelated—William James’s “blooming, buzzing confusion.” Without the instance, all phenomena would appear the same and interchangeable. This, then, shows us in the brief moments of perceptual awareness one example of the much more pervasive philosophical question of the relation between identity and difference, not as a logical, formal problem, but as a constitutive feature of perception as such.

It is not too much to say that the antinomies of philosophy—one and many, identity and difference, being and becoming, particular and universal—are at play in the subtle texture of perception itself. Already here in perception do we find the work of Heraclitus and Parmenides in tension, the contest between flux and permanence, before we’ve attempted to say anything at all. In this sense, all philosophy, at least in part, is always phenomenology, whatever else it might be.

And this observation raises for us the following questions: What are we doing when we examine the phenomenology of perception in this way? What activity are we engaged in when these memory-images fail to grasp the phenomena in question? What do we do when there are no adequate memory-images to choose from? We would enter into a field that is neither the automatic recollection of habit nor the intellectual work of deliberately calling forth a representation adequate to our circumstance. I’ll propose that the answer to this question is “thinking,” in the particular way I’ve described it above—as composed of ekstasis, theōria, and poēsis.

From here, we can put the situation more plainly: Thinking is what happens when we do not know what to think, when we do not know what we’re perceiving.

Another way to say this that differentiates the two meanings of “thinking” in this statement would be: Thinking is what happens when we do not know what to recall, represent, or repeat. If we take recourse to memory—to our stock of extant knowledge, concepts, and representations—then we should not call this activity “thinking” but remembering, applying, or rule‑following.

For this reason, thinking can only happen in a field where existing concepts, feelings, and sensations lack purchase on a phenomenon or event. The precipitating event is something singular—the first of its kind, at least for that perceiver—and the thought that meets it must be likewise singular. If the event resembled past experience closely enough, we wouldn’t think; we would simply recall the concept, the kind of thing under which it can be classed, and perceive the event in those terms. If, however, what we encounter has no existing corresponding concept, then we must think outside of this storehouse of ideas and memories.

How, then, are we to think about thinking in this context?

3. The Interruption Called Thinking

Not, as I’ve just said, by identification and recall, but through some other means. Gilles Deleuze, drawing in part on Bergson, notes that thinking does not begin in recognition. It begins when something shocks thought into motion—an encounter with a sign, an event, an intensity, an anomaly that cannot be subsumed under available concepts, forcing thought beyond its usual complement of ideas. Concept creation emerges in just this encounter. This would be a thinking that is not yet representing—and may not even aim at representing—a thinking that is something other than following an existing procedure or system of pattern matching.

All of this brings us to another simple claim: The meaning of thinking is its non‑repeated nature. In other words, its uniqueness is the very essence of what thinking is.

In this way, thinking is what stands outside of repetition—or at least, breaks free from it for a moment—and therein we find the reason for its value. Thought can be both singular and abstractly general, singular in the sense that it arises only once in this exact form, yet abstract in the sense that it can give rise to concepts or ideas that transcend the moment of their creation. Its value emerges from this non‑repeatable character. In other words, thought, insofar as it is thought as I’ve described it, is 1‑of‑1. By definition it is scarce.

The economists would describe thought as non‑fungible; it cannot be traded in for another item of its kind because there is no other item of its kind. Even the recall of a thought one has had is different from the thought when it first arrived. It only happens once—hence the importance of needing to write it down before it slips away. Does this mean that every thought will be insightful, useful, or interesting? No, of course not. But in the ecology of mind, thought is the rarest of creatures, as each thought is, perhaps, its own kind. It only later becomes a concept—the means by which one may have the thought again, as a type of memory—bringing it into the level of established ideas available for recollection or circulation or education.

If this is right, then:

Thinking is not a repetition of the same; it is not simply the application of identity. That activity is better called recall or representation.

Thinking is not inarticulate or disordered; it is not merely an awareness of sheer difference. That state is better described as confusion or wonder.

Thinking is not calculation; it is not only the mechanical application of rules or concepts. That belongs to procedure, not to thought.

Identity and difference as limit concepts can certainly be ingredient in thinking, but if thinking is fully neither (1), (2), nor (3), then the negative space left over must hold at least some shade of our answer. I believe part of that answer is creation, generation, life, novelty—poēsis—a kind of creation beyond recombination.

4. Waiting for the Birds

This involves, centrally, a kind of contemplation—a receptive waiting at the steps of confusion, of the failure of our concepts. Originally, a “templum” was an instrument used in augury to mark out a space in the sky, forming a kind of clearing. The augur would literally “cut” the sky into quadrangles with his staff, then sit and watch for the flight of birds, noting their number, direction, and behavior as signs. Contemplation, in its root sense, then, is something like “waiting for the birds”—the discipline of resting, observing, and waiting for what might appear within the clearing.

When we do not yet have the adequate concepts, we must release the errant flow of pattern‑matching and wait—for what? For new signs, for hints of meaning, for symbols more adequate to what we’re trying to understand. This waiting, this resting, this contemplating is, I think, one of the preconditions for leaving the field of representation and memory, letting it fall by the wayside as we move outward beyond the field. And it is in that “beyond” that the next movements—ekstasis and poēsis—become possible.

Insofar as this is possible, thinking stands outside of repetition through a kind of contemplative suspension or patient waiting—or at least it breaks free from repetition for a moment by letting go of, or releasing, the project of representing. In this process, we find its true character. It is essentially ecstatic (in the sense of ekstasis—from Greek ek “out” + stasis “standing,” literally “standing outside”).

Thinking is going outside of ourselves, outside of our memory and perception, back into the unknown outdoors, and back in again. To think, then, is to move outside of repetition into creation, poēsis. Here we come closest to what Bergson called intuition—not the intellect’s analytic parsing, but a direct, creative sympathy with the flowing stream of activity around us. Intuition, for Bergson, is the act of entering into the movement of life itself; and poēsis, in the sense I’m using it, is the outcome of that sympathy, the moment of a new thought form or concept in its genesis.

Thus we can say of thinking that it is contemplative, because it requires preparatory waiting and receptivity; ecstatic, because it requires stepping outside the field of memory and repetition; and poetic, because it requires the creation of new words, concepts, or images. Bergson himself doesn’t give us this account of thinking outright. What he offers instead is a map of this landscape of memory, perception, and duration. I’ve used that terrain to work via negativa and shade in what thinking might look like when it doesn’t operate in this space of repetition, memory, and perception.

If Bergson shows us how deeply memory saturates perception, then this sketch asks what might happen when we break with the saturation of representation that colors our everyday perception, when there is no ready memory‑image to call upon. The answer, I’ve suggested, is a form of thinking that waits, exits, and generates, a thinking not of recall, but of creation.

To think is to create.

This is wonderful, thanks for sharing! I do have one question about poiesis and repetition. Coming at it from how I think Bergson might’ve looked at it, is it that thinking steps out of repetition, or that there is ontological repetition in the sense of Deleuze’s eternal return of the Same, where what is repeated is difference in-itself, which doesn’t efface the past, but does something new with it? This comes mostly from my skepticism about whether creativity is possible without memory, however I do sympathize with the desire to cultivate a kind of non-conceptual awareness of the present like what you find in Zen, for example, though I do struggle a lot with this, and it’s something I actively try to reconcile with Bergson’s metaphysics.

This is an excellent — and thought-provoking! — meditation on thinking. Thank you for sharing this.